We propose the summary of an article written by Penelope Campling, entitled “Reforming the culture of healthcare: the case for intelligent kindness”, published by the BJPsych Bulletin.

This editorial makes the case for a more conscious and active focus on the concept of intelligent kindness in all parts of the healthcare system. It starts, however, by exploring the forces that create perverse dynamics that can pull in the opposite direction.

Studies suggest that the majority of healthcare students are motivated by the wish to make things better, but during their training become more distanced from patients and less empathic. Raymond Tallis, British philosopher and retired professor of geriatric medicine, comments on the enormity in the history of civilisation of the imaginative and moral step involved in engaging with the realities of illness. He describes a challenging process of cognitive self-overcoming on the part of humanity and reminds us that humans found it easier to assume an objective attitude towards the stars than towards their own inner organs.

Contact with emotional distress and disturbance can be equally, if not more, harrowing. Existential questions about identity, suffering, madness and death are raised and may put people in touch with extreme feelings of confusion, pain and loss. Psychological defence mechanisms are evoked frequently. Problems can arise if staff are exposed to frequent emotional trauma, without space to process their feelings. Defensive styles of coping then become entrenched. As defensive walls build up, feelings of vulnerability and sadness become more deeply buried and the capacity for empathy recedes.

Attachment to a well-functioning group can help to contain disturbed feelings and facilitate a healthy focus on the emotional task, but groups can also be the scene of disturbed – often unconscious – dynamics. Many staff, particularly senior staff, have a peripatetic role and belong in many different ‘teams’. Although most hospital staff say they belong to a team, Borrill et al show that more than 60% are in what they call pseudo-teams, with no obvious cohesion or boundary.

The health service sits within a broader society that shapes its rules, agreements and unconscious social pacts. The spirit of cooperation that was around in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War provided a fertile value base for implementing the NHS, but has been steadily encroached upon by individualism, consumerism and the hegemony of market forces. Susan Long describes and gives evidence for this in her book The Perverse Organisation and Its Deadly Sins. A basic premise of her book is that there has been a move in society generally from a culture of narcissism to elements of a culture of perversion. Perversion flourishes where instrumental relations have dominance – in other words, where people are used as a means to an end, as tools and commodities rather than respected citizens.

It is important to realise that Long’s emphasis is on perversity displayed by institutions rather than by their leaders or members. There is no suggestion that individual NHS workers, as people, are any more perverse than workers in any other organisation. The concept of perversion sheds light on frankly exploitative behaviour, helps explain how many people in positions of trust end up abusing those positions and how people may be collectively perverse despite individual attempts to be otherwise.

In the light of the present crisis in the culture of our healthcare system, it is particularly important to be able to talk in terms of positive values, to have a clear vision of how we would like to see our organisations function, how we wish to encourage society – and the organisations that serve society – to relate to the sick and vulnerable. A number of writers and philosophers have attempted to address the worrying narrowing of the moral universe in organisational life: Paul Ricoeur refers to the loss of ethical intention in public life. Clearly, there is a large overlap between the concept of compassion and the concept of kindness. Both words are defined in relation to other people: compassion literally meaning ‘suffering with’ whereas kindness is linked to the concept of kin and kinship. Kindness is a word very commonly used by patients. Many people’s stories about their experience of healthcare centre around the degree and quality of kindness they have (or have not) experienced. Often these accounts are complaints about the absence of kindness, the thoughtlessness, the lack of humane care. Sometimes they describe the power of small, but highly relevant, acts of kindness to transform an otherwise miserable experience of suffering.

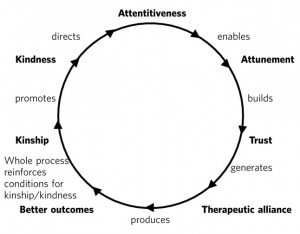

Kindness has its roots in the Old English word cynd – meaning nature, family, lineage – kin. Kindness implies the recognition of being of the same nature as others, being of a kind, in kinship. It implies that people are motivated by that recognition to cooperate, to treat others as members of the family, to be generous and thoughtful. Then we can add the adjective “intelligent”. Intelligent kindness, then, is not a soft, sentimental feeling or action that is beside the point in the challenging, clever, technical business of managing and delivering healthcare. It is a binding, creative and problem-solving force that inspires and focuses the imagination and goodwill.There is a body of evidence that supports this virtuous circle. Simply put, the more attentively kind staff are, the more their attunement to the patient increases; the more that increases, the more trust is generated; the more trust, the better the therapeutic alliance; the better the alliance, the better the outcomes. The result of all this is a reduction in anxiety, improved satisfaction (for staff and patient), less defensiveness and improved conditions for kindness.

Kindness rooted in kinship is a powerful concept – ethically, politically, socially and clinically – in the project of improving healthcare. It increases patient satisfaction, staff morale, clinical effectiveness and efficiency. But virtuous circles are vulnerable and we know from history how quickly a benign culture can become malignant. The virtuous circle described here earlier could provide a basis for thinking about this, strengthening relationships between colleagues and with patients, and counteracting the pressures to adopt instrumental attitudes to the work that are all too prevalent at the present time. At an anecdotal level, individuals report that the concept of intelligent kindness properly embedded in reflective practice has ‘reconnected them to their altruism’; and teams from ward to board level have found the virtuous circle a helpful focus when thinking about culture change. There is scope for adapting the model for research and audit purposes, building on the evidence base for relational science to influence the organisation of healthcare delivery and outcome.

Kindness rooted in kinship is a powerful concept – ethically, politically, socially and clinically – in the project of improving healthcare. It increases patient satisfaction, staff morale, clinical effectiveness and efficiency. But virtuous circles are vulnerable and we know from history how quickly a benign culture can become malignant. The virtuous circle described here earlier could provide a basis for thinking about this, strengthening relationships between colleagues and with patients, and counteracting the pressures to adopt instrumental attitudes to the work that are all too prevalent at the present time. At an anecdotal level, individuals report that the concept of intelligent kindness properly embedded in reflective practice has ‘reconnected them to their altruism’; and teams from ward to board level have found the virtuous circle a helpful focus when thinking about culture change. There is scope for adapting the model for research and audit purposes, building on the evidence base for relational science to influence the organisation of healthcare delivery and outcome.