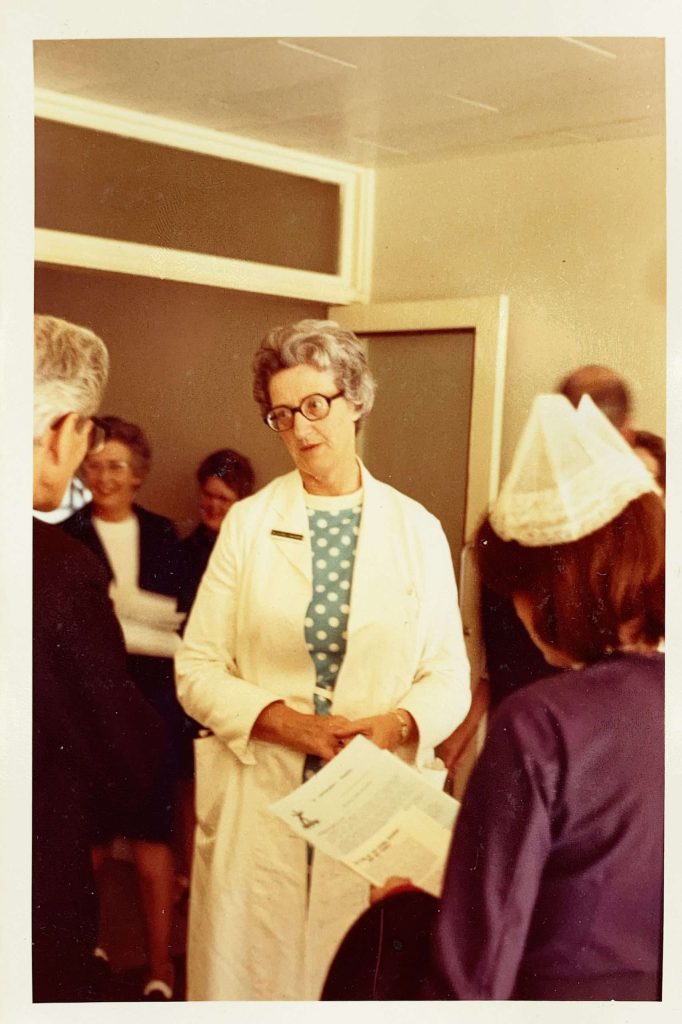

Twenty years after Cicely Saunders’ death, which occurred as she wished in her St. Christopher’s Hospice in London on 14 July 2005, a question arises: what, of her material and spiritual legacy, is still relevant today in the vast field of Palliative Care, so much so that she is recognised worldwide as the Founder of the modern Hospice Movement?

Talking about Cicely Saunders – first a nurse, then a social worker and finally a doctor – is for me an honour and a commitment: ever since I ‘met’ her in 2008, at a course for hospice volunteers, I felt a deep attraction for her charismatic and visionary figure, yet so human, real and authentic… as if her well traced steps, but still little known in Italy, were crying out to be told so as not to be forgotten or buried in the past. What is authentic, in fact, always remains intrinsically current and with a precious message to be declined in every era.

Here, then, in synergy with the Association ‘On Cicely’s Path’ for the cultural and social promotion of Palliative Care, it is a pleasure to highlight some traits of her journey and some aspects of her personality that can still speak today to those who work in the field of care, but not only: starting from young people in schools to the elderly, her message radiates like the clear light of a lighthouse to illuminate the darkness of illness and death, charting a course that can lead to port even in the midst of stormy waves.

Cicely was, first and foremost, a woman capable of transforming difficulties and obstacles into opportunities for growth and change: how many times in the family, at school, in health problems or at work was she able to learn from experience, without fear of going against the ‘mainstream’? Determined, sometimes a little stubborn, but with that fascinating habitus of humility, honesty and awareness that characterised her until the end, she always asked if ‘enough had been done’ to meet the needs of those who could no longer heal. Despite the extraordinary results of her work and commitment, she felt that every point of arrival was a new departure, and, with a healthy dose of realism and confidence, she set out again.

Even her last years as a breast cancer patient were an ongoing learning curve, by no means easy, as for all those she had accompanied over time: genuinely painful, as she herself recounts, but at the same time soothed by the balm of the many relationships of friendship and affection she had cultivated, devoting quality time to them.

The veracity of all this was astonishingly confirmed when I had the privilege of meeting Cicely’s younger brother Christopher (already 90! ), and to have a long conversation with him, first by email and then in three live meetings in his small house in Cambridge: to receive the affectionate and moving testimony of such a close family member, who helped her concretely to build her hospice and facilitated her, through his contacts, to undertake her first trips overseas, proved to be the gift of touching, once again, the authenticity of what I had intuited, read or heard about her… Thank you, dear friend!

Cicely is still convincing today, then, precisely because she experienced at first-hand what she believed in and testified to it by her confident ‘being there’ in the time of trial: she was not exempt, that is, from the kind of ‘total pain’ – physical, emotional, spiritual and social – that required ‘total care’, tailored to the personal needs of each patient. “We treated her well, and she told us we treated her well,” testified Barbara Monroe, then Chief Executive at St Christopher’s.

Undoubtedly, her credibility also comes from her being a visionary, but at the same time concrete and realistic: the dream that began to take shape in 1948 thanks to the intense spiritual conversations with David Tasma – the first ‘founding patient’ of the Hospice – was enriched with pieces steeped in humanity and creativity in the encounters with other ‘milestones’ of this exceptional Foundation, such as Antoni in 1960, until it succeeded in a feat never achieved before. St Christopher’s Hospice was the fruit of teamwork not without its slips, but imbued with conviction, enthusiasm and faith in a grandiose, if mysterious ideal.

What can we say then about how, even today, we can and should be inspired by her in placing patients with their stories at the centre and in the attentive listening she offered to create a familiar and serene environment like a home, where they could rest easy?

And then again: there was not only tenderness and hospitality in her Care Handbook, but also a great deal of expertise, scientific skills, drug experimentation, research and continuous training, at the patient’s bedside and in the laboratories; because there is no heart without a mind, nor mind without a heart in the care that she wanted and claimed to be the Hospice’s hallmark. He maintained, in fact, that those who worked there had to do so with love, which is also true today.

An indefatigable worker, travel lover, lecturer and writer, she loved art, poetry, music and her husband Marian‘s colourful paintings, because she was convinced that they were tools as powerful as medicines in relieving pain and soothing hearts: the regenerating power of Art Therapy and the Medical Humanities, now scientifically proven, already found in her a pioneer and a credible witness.

An exceptional scientist and a woman of great culture, she knew how to ‘be there’ for anyone who needed her, without prejudice and without judgement, sharing tears, but also laughter, moments of joy and home-made cakes… Small, great ‘crumbs’ of authenticity, when all that remains is the essential.

Cicely was thus the first true Professional to dedicate her entire working career to the dying, while doctors by practice neglected them; she certainly did so on the wave of examples from the past, which she recognised and contextualised, but with that uniqueness and contagious vitality that still questions and stimulates us today. Thank you, Cicely!