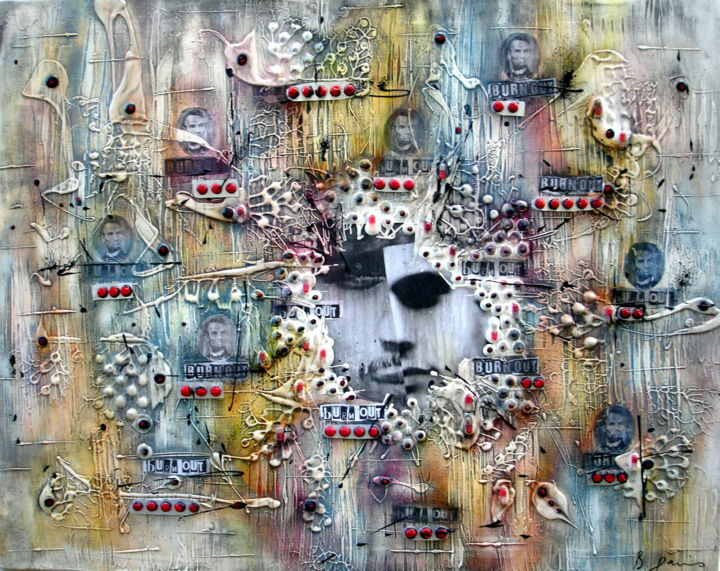

Acrylique et techniques mixtes

On May 30, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized burnout as an occupational and multifactorial syndrome, worthy of attention as it is characterised by a rapid decline in psychophysical resources and deterioration of occupational performance. Burnout is included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as an occupational phenomenon.

Over the past year, billions of people around the world have experienced chronic stress at work, at home, and in their communities. They have struggled to change their work routines. Many people have continued their work routines while caring for children or the elderly, or even studying remotely. Many people continued their work availability while grieving the loss of loved ones in a dramatic situation.

Given the multiple challenges, the current increase in burnout rates should not be considered so much an individual failure to manage chronic stress such as that in the pre-Covid-19 era, but a new specific form of burnout with its own causes and impacts. Pandemic-related burnout requires a different approach, both in terms of prevention and mitigation.

Why is pandemic-related burnout different from other forms of burnout?

On the one hand, as with other forms of burnout, it is associated with feelings of exhaustion or loss of energy; increased mental distance from one’s work, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s work and reduced professional effectiveness. However, new pandemic-associated burnout is more difficult to detect because, during the pandemic, symptoms of it were devalued and viewed as a normal, responsible reaction to what was happening. In fact, most people were pushed to accept the idea that feeling depressed, isolated, or anxious is just “something to live with.”

A June 2020 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted to assess mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the pandemic among adults aged ≥18 years across the United States during June 24-30, 2020, found that 40.9% of respondents had at least one adverse mental or behavioural health condition, including symptoms of an anxiety or depressive disorder (30.9%), symptoms of a disorder related to pandemic-related trauma and stress (26.3%), and having initiated or increased substance use to cope with stress or emotions related to COVID-19 (13.3%).

In the months that followed, the situation became increasingly dire. A December 2020 survey by Spring Health suggests that the number of Americans experiencing burnout could be as high as 76%.

If the situation is dramatic for all professions, it is even more so for healthcare professionals.

One of the heaviest consequences of the spread of COVID-19 is the very health crisis that is afflicting health systems around the world. Regardless of job description and role type, health professionals are called upon every day to confront an emergency that burdens their own health. The rapidity of the spread of emergencies, their impact at different levels on health and the organization of life, as well as the persistence of these challenges over time, have put health professionals in the position of having to live with all those inconveniences in an extraordinary and sudden way. Add to that stressful shifts, staff shortages, on-call availability and constant contact with pain and suffering. Moreover, fear and concern about contagion for themselves and their loved ones have led many health professionals to protect themselves by self-isolation, manifesting additional symptoms related to intense psychological distress. With this in mind, it becomes essential to balance one’s energy accounts on a weekly basis.

Before the pandemic, burnout was already a significant problem across all industries. It cost organizations an estimated $125-190 billion per year.

However, it must be said that some professions are particularly vulnerable to burnout: that of physicians alone costs $4.6 billion per year. From 2020 to 2021, the cost of burnout is expected to be much higher.

For institutions, the challenge within the challenge is to address pandemic-related burnout before it occurs, requiring greater self-awareness and planning.

How to find an escape from pandemic-related burnout?

For health professionals, when you’re exhausted, depleted and overloaded, it can be difficult to find the motivation to take control of your own health and well-being, and carving out time for yourself can seem selfish. In reality, it’s the perspective from which to start over in order to truly be there for each other. Taking breaks from work, going out for a walk or for fresh air, practicing physical activity improve both our physical state and our mood. It can also be helpful to figure out what we like about work and focus on our interests and passions. Another possible strategy is to ask for help from colleagues, family members, friends, also showing your vulnerable side and without wanting to continue to be a superhero.

We all wish for this pandemic to end. There are also some things that we discovered we were capable of doing during the pandemic and would like to carry over into the aftermath such as, for example, cooking at home, the importance of cultivating friendships even if they are distant, the love of reading…and others that we have realized are not as relevant such as, for example, alienating ourselves in and out of online meetings without the time, where we hail the recovery of efficiency and not effectiveness. Let’s take some time to celebrate what the pandemic has taught you and how it has changed us, our family, our team or our organization for the better. This will be for the overall benefit of building post-traumatic growth rather than post-traumatic stress.