The word science comes from the Latin scientia, a derivative of the present participle of the verb scire (to know). Its root can be traced to the European proto-indo *sēik- which has the meaning of “to cut.”

The Latin word translates the Greek episteme (ἐπιστήμη), which is composed of epi (on) and histamai (to stand, to place, to establish), for the overall meaning of “holding on to itself.” The word initially indicated “any knowledge enabling one to perform certain activities or trades, and later, more specifically, the rigorous and theoretical aspect of knowledge, as opposed to both δόξα (opinion) and ἐμπειρία (empirìa), which indicated only the operational capacity” (Treccani).

In Latin, therefore, the word scientia inherits the Greek meaning and indicates a systematic and coherently formulated knowledge. This meaning includes both the so-called “natural sciences” and those called “moral sciences“, coming to express a comprehensive and articulated knowledge.

With the modern age and the scientific revolution first, then the Enlightenment and Positivism, science loses its sacred character and is inextricably linked to the question of method. We pass, therefore, from a concept of systemic knowledge to a methodical one, from valuing the links between the various fields of knowledge to focusing solely on the “natural sciences”, studied according to a method that brings conceptual acquisitions that are determinable and directly verifiable by means of appropriate empirical experiments. The science that sees man as the protagonist, is replaced by an approach that wants it as much as possible to delete.

This leads to the twentieth century, where the “crisis of fundamentals” and the work of thinkers like Karl Popper lead to the decline of the paradigm of absolute truth of science in favor of a more conjectural conception. After Popper, the epistemological reflection comes to undermine the very concept of method and therefore the idea that science is a privileged and untouchable discipline.

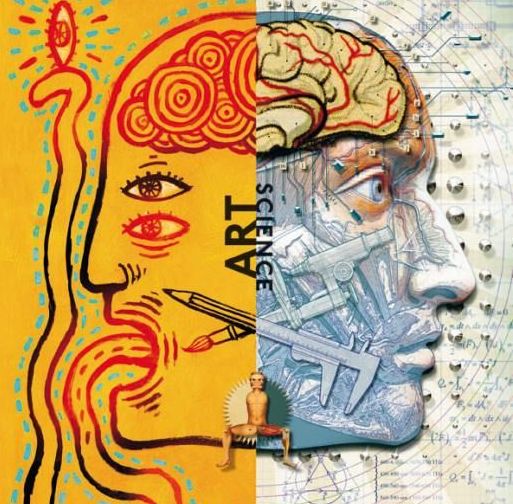

Taking up its history and etymology, one can refine and problematize the concept of science, observing how it is only with the modern age that the moral component was lost and the paradigm of method was stiffened. Now, it would be wrong not to recognize that the scientific method has not led to discoveries and theories that have greatly improved our quality of life, however, it should not be absolutized and exempted from any criticism and problematization. What perhaps needs to be focused on more often is the recovery of the ethical and humanistic component of science, which only five hundred years ago were abandoned and then work on their reintegration into the scientific paradigms, so that human and methodical components return to coexist in the concept of science.

Once this is done, it must be recognized that scientific language is specialized and therefore difficult for non-experts. Therefore, having re-established the ethics of science, we must work to find new channels and languages of communication.

Please leave us a word for your feelings about science.

Thank you Enrica! A really fascinating exposition. If u haven’t read Bhaskar I think you’d enjoy his writing. Love the way u linked a relational approach to science with a moral one as opposed to the atomistic positivism. Thank you. Rod

Wonderful, Hazza!