We host the project work by Carla Galvani, participant to the 4th edition of the Master in Applied Narrative Medicine at ISTUD Foundation.

In every society, forms of pervasive control in every aspect of women’s life correspond to pregnancy and childbirth. Because it’s a potentially dangerous phase, this control assumes the meaning and the form of reassuring protection.

In Italian society, the medicalization of pregnancy and the hospitalization of childbirth constitute the forms of control employed to ensure that the event will happen according to preset ways, independently by the willingness of the individual [1]. Symbolical constructs are realized in pregnancy and childbirth, and are necessary to maintain medical power and legitimacy in the control of reproductive process. According to Elena Balsamo, symbolism is a tool of social control, and becomes stronger in condition of danger such as childbirth [2].

When the sense of social order is threatened, borders between individual and political body blend, and a renovated interest spreads out, often expressed in the surveillance of social and physical borders – not only of individuals but also of population, and therefore of sexuality, gender, reproduction [3]. This form of protection/control is so integrated in our culture that we don’t even realize it. When an Italian woman gets pregnant, the first thought is not about risk, but other categories of problems. Only secondly emerges the concern that the event might end badly. In fact, dying in childbirth creates stir.

In several zones of Africa, the sensation of danger is very strong and pregnancy and childbirth are collectively lived. Since the first months of pregnancy, control, management, and support are entrusted to the community of gender, of the parental group: grandmother, mother, sisters.

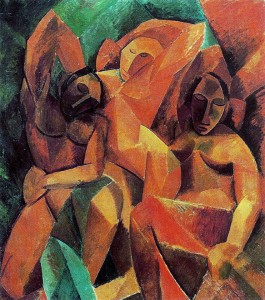

In African cultures [4] childbirth is assimilated to a rite of passage for both woman and child. Pregnancy and childbirth are the first event of the individual life that upholds the entrance in the community. From a person are generated two persons. Woman is born again in a new condition, becoming mother. Symbolically there is an overlap between maternal and childish that allows women to think about themselves as mothers. The child enters the family and the community. Perils of pregnancy concern both mother and child. In situations of crisis and poverty, as in some countries of Central Africa, children with sickle cell anemia, epilepsy, or behavioural disorders, are subjected to heavy stigmatizations, as the exclusion from instruction and hospitalization, too much expensive; they can be abandoned in the street or in the forest, because they are considered object of witchcraft. A work by Doris Bonnet [5] on the condition of patients with sickle cell anemia (SCA) evidences problems linked to the identity process. Women with SCA are often considered “jinx”, cursed women. The theme of curse, present in tribal Africa, is essentially attributed to women repeatedly damaged in the reproductive sphere. Sometimes they are repudiated. The habit to think to curse, in some African regions (mostly in Sub-Saharan area, where nomadism is active and the prevalent activity of subsistence is the livestock farming), doesn’t damage only women and sick children, but stigmatise also men that live with women dying of childbirth.

The migration to Europe and the access to public healthcare and genetics has allowed this people to reconstruct the history of the disease, the family tree, to reconfigure the relationships within the family group (e.g. inbreeding) in new countries.

The joint participation of the couple to the transmission of the disease brought on the scene the joint responsibility of the man in familiar transmission. Some men, and even more the family of origin, don’t accept the Mendelian vision of the genetic transmission. The lacking knowledge of the social organization of African popular societies by healthcare professionals, brings them to use the concept of “culture of origin” to explain behaviours (in particular the scarce adherence to treatment) of immigrant people otherwise considered incomprehensible. The concept of “culture of origin” applied to contexts really different between them can become a generalization that cancel social diversity and the migration and integration stories that each one presents. The generalized use of this notion doesn’t allow to know changes in social and familiar structures of all countries of Sub-Saharan Africa. The pertinence of contextual analysis, the research, the investigation open to knowledge and comprehension. It’s a long process of integration and cultural reshuffle that concerns migrants and western operators.

Sickle cell anaemia is a genetic disease that damages haemoglobin; it’s characterized by chronic anaemia (lack of red blood cells and haemoglobin) and painful acute episodes, with damage of districts and organs. The disease takes its name by the sickle shape of the red blood cells of affected people, and is particularly frequent in the Mediterranean regions and in Sub-Saharan Africa.

This disease doesn’t have the same clinical progress in all the patients: some people show minor ailments, while others show severe symptoms.

My project work at the Master in Applied Narrative Medicine

In the last years of my working career as a physiotherapist at the Day Service of Internal Medicine of the General Hospital of Verona, I have occasionally followed some pregnant women with SCA during recoveries due to vaso-occlusive crises.

I’ll never forget those confused eyes full of fear. Working on the project work during the Master in Applied Narrative Medicine at ISTUD Foundation, collecting their narratives appeared to me as a possibility to know and give voice to those fears. Narratives were collected through conversations (semi-structured oral interviews) with women that experienced pregnancy from 2010 to 2015. The choice of this time interval is based on the characteristic of disease, that limits consistently patients to face a pregnancy, as well as conception is difficult.

I let the narration free, using questions as support in cases in which the speech was difficult. In some case narrative was fluent, in others I employed some questions, in others I let the speech as it was.

Main themes concerned:

The culture of the place of origin: In Burkina Faso is normal to suffer during pregnancy when a woman has SCA. They know that it’s dangerous, they fear the childbirth; In Ghana SCA is a “stigma”… In Africa pregnant women suffer more than here in the West, they spit a lot and for us it’s normal. We accept it.

The fear to transmit the disease to the baby: My main fears were to transmit the disease to the baby and to not carry the pregnancy to term; Inside of me I was thinking “If even this child is sick, I will kill me”; The baby is healthy, she doesn’t have SCA. I was relieved when I heard it; This fear has accompanied me for all the pregnancy.

Solitude: I was keeping it all inside. I had a sad gaze. For this I had several crises; I didn’t have real friends, even now I don’t; I have never talked about my real preoccupation; I have never talked with anyone about my thoughts and preoccupations, I don’t trust anyone, it’s like to be alone.

Emotions declared were:

Fear: I feared to lose the baby; I was worried for my health, and I was wondering “Will I be able to carry the pregnancy to term?”; I had two fears. The first, to lose the baby; the second, that he could be abnormal, with severe malformations, with all the medicines I took… I didn’t want to lose him, and I didn’t want him to have severe handicaps. If it was that danger, it would have been better to follow Nature’s course; I felt really weak. I believed I was dying. We were desperate.

The joy to feel inside a new life: The most emotional moments were the first ultrasound, I saw him for the first time, and the first movements, his presence and the birth; I was impressed by knowing that she’s my daughter, I did her; Now I understand my mother when she tells me “I love you”.

The need to trust and feel reassured: I was worried, the other women reassured me; Here they are human and careful to people. I don’t have to worry about anything, they call me at home.

The desire to be able to do it: When he was born I thought “I did it”… I cried for joy.

The need to share with other women and to build up a support group to facilitate discussion, sharing and exchanging of experiences: I don’t easily socialize, I need time, but I would have like a discussion with other women; I didn’t have contacts with other women facing my condition, I would have like sharing my experience and reassure; I met a patient of the centre, African like me, she had already had children. It was a casual encounter, but really helpful. She told me her experience, I made her questions, she gave me advices. She reassured me; I liked to narrate, maybe it will be helpful for other women; It would be great to have the possibility to discuss, children grow up and there always are new questions; It would be helpful to organize some meetings with women with SCA, even those who don’t have children yet, to talk and show that others’ stories can be helpful.

Almost all refer to their husbands: This time I was with my husband, and the burden of this situation was share; My husband was close to me; My husband asked where we could find help for my case.

Listening to these stories, I relived my maternity experience. I perceived my ignorance, my gross knowledge of immigrants’ worlds, I felt the ease with which you can goof in a defensive manner in the concept of “culture of origin”. This work has been to me like a new pregnancy, with the fear of not succeeding, of generating a defective and deformed “product”, but with the hope that all was good and that the ideal child was not too dissimilar from the real baby. Each project is a generative process, and in this sense compares genders.

Furthermore, this work has intended to represent a first occasion of discussion between women facing this delicate experience, with the willingness to structure it in a real support group, as requested by women themselves. Narrative, in any culture and language, is a bridge that opens, sustains, and can only bring in a good direction.

[1] and [4] Colombo G, Pizzini F, Regalia A. 1985. Mettere al mondo. La produzione sociale del parto. Milano: Franco Angeli.

[2] Balsamo E, 2002. Bambini immigrati e bisogni insoddisfatti: la via dell’etnopediatria”, in Balsamo E, Favaro G, Pavesi A, Samaniego M. Mille modi di crescere. Bambini immigrati e modi di cura. Milano: Franco Angeli.

[3] Lock M, Scheper-Hughes N, 1987. Un approccio critico-interpretativo in antropologia medica, in Quaranta I, 2006. Antropologia medica. I testi fondamentali. Milano: Raffaello Cortina.

[5] Bonnet A, 2009. Repenser l’Hérédité. Paris: Editions des Archives Contemporaines.