In seminars of narrative medicine, illness centred movies are widely used to show with vivid images and sounds a plot which narrates how persons living with a particular condition of impairment go through the pathway of care; movies show also how the people around as relatives, parents, friends, colleagues, and “the others” react to the disease. Generally, in cinema, emotions are so strong to move by, and induce sorrows up to tears, especially if the ending is a sad one, or rejoice when there is a happy ending, the desired healing process.

In seminars of narrative medicine, illness centred movies are widely used to show with vivid images and sounds a plot which narrates how persons living with a particular condition of impairment go through the pathway of care; movies show also how the people around as relatives, parents, friends, colleagues, and “the others” react to the disease. Generally, in cinema, emotions are so strong to move by, and induce sorrows up to tears, especially if the ending is a sad one, or rejoice when there is a happy ending, the desired healing process.

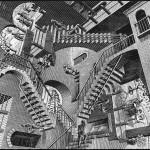

In pedagogical matter, these movies are perfect architectures of didactic cases and able to open with smooth and soft keys the “hearts” of the evidence bases health care providers, beyond the hearts of common people. Cinematic is very powerful in this, unless a boomerang effect is originated: after too many tears, the pure scientists want to go back to their odds and probabilities, confidence intervals, made by numbers and statistics.

Some of these movies are openly declared as fiction, as the sharp and sweet “The barbarian invasions“ by Denys Arcand or the visionary “Big Fish” by Tim Burton, both on the “dying”, the “leaving this world”, but other plots are instead declared to represent a real story, or, in the most accurate and transparent definition, to be based on a true story of a disease.

When we watch “Patch Adams“, we know that it is inspired by a true story of Hunter Doherty Adams, the inventor of the clown therapy, but we acknowledge immediately that there is also a distortion form reality due to the storyboard and to the genius and spontaneousness of Robin Williams.

In Italy, we are proud to have given birth to a great war journalist, Tiziano Terzani who died for a cancer lasted seven years, a period in which Terzani tried all the Occidental and Oriental possible remedies of care: in a direct interview documentary over the last months of his life, he narrated his biography. The video was really intended to leave to the others his last thoughts and his last willingness. Later, after his death, his son, Folco Terzani, out of the documentary that he shot, decided to make a movie: “La fine è il mio inizio”- “The end is my beginning” a very touchy movie indeed. Folco Terzani declared that through this cinema making he was able to reconcile with his father after his death. The movie was almost a copy of the documentary: the actor was an extraordinary Bruno Ganz…. But… after having seen the real documentary, fiction was pervading the movie, despite shots were taken in the real sites where Terzani lived the last months: Bruno Ganz was not affected _ hopefully_ by a cancer and as spectator, one could feel that the actor, despite the huge efforts of the make up, his voice and his breath were not those of a person with a late stage cancer and especially not mirroring the real video of the journalist. Nevertheless the movie is indeed worth to be seen, but not influential as the true interview, much more powerful to use as a didactic and inspiring case.

But there is a more striking and interesting case in which I, personally, felt fully in the trap: the Strange Case of “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly”, “Lo scanfandro e la farfalla“, a French movie directed by Julian Schnabel. This movie deals with the story of Jean Dominique Bauby, a successful editor – the director of Elle France – who suddenly had a stroke which impaired him and constrained him to live the “locked-in syndrome”. In his disease every side of the body was paralysed and the only part which was left free to move was an eyelid. And just with an eyelid and a special alphabet he learnt how to communicate and dictated his diary to a volunteer who was assisting him while he was in the rehabilitation centre at Berck-sur-Mer. The diary is breath taking: the coping strategy of this man is incredible- two things are left healthy after the accident: Jean Dominque’s memory and imagination and with these two faculties he could remember all his past and with imagination he could go and be everywhere… and these two forces gave him the willingness to live even in this extreme situation. Bauby died soon after the publication of the diary.

I read the diary after having seen the movie: what did I remark? No major big differences, but on the contrary I found a tremendous consistency between the written autobiography and the cinematic. My mind set was focused on two main findings: the pathways of care, and the coping strategy. I was not puzzled by what was happening to the characters… whereas indeed something happened.

The heirs of the copyright of the diary were the two children he had with his ex-wife, Madame De La Rochefoucald, from whom Bauby was separated. Since the children of Bauby were still minor, Schnabel and the plot maker should have been consulting De La Rochefoucald for asking the permission to shoot the movie and for alignment of the story plot.

Bauby, at the moment of the disease had a new girlfriend, Florence. In the diary the focus is not so much on the women of his life but on the caregiving at the hospitals and particularly on the experts care who teach him how to communicate, and not to be isolated from the world. Let’s consider, he was a journalist, he had chosen vocationally a profession of communication and people contact: the absence of communication would have probably been the deepest loss of his daily practice.

In synthesis, as in this article http://www.salon.com/2008/02/23/diving_bell_2/ reported, De La Rochefoucald could have manipulated the whole truth in the storyboard of the movie, becoming her the main caregiver at Berck, whereas in real life it was Florence the person who regularly visited Jean Dominique in the rehabilitation centre. In the diary it is reported that the ex-wife came only once, during the weekend to let see the children to the father. It could have been a sort of revenge brought to the public and naïve audience, who did not know anything about the family.

The “take home message” is therefore to be cautious when considering and analysing illness movies as part of narrative medicine: they might be inspired by real stories but they often do belong to romantic genre, brought into the medical humanities, not as clean “narrative medicine” which is, according to the published definition, a collection of true stories of illness. Rita Charon teaches us to honour the stories of illness, but how is it possible to feel respect for such a revenge behaviour as that shown in the strange case of “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly” movie making?

On top of this fact, there is another issue which is very intriguing: George Simenon in his “The Patient”, or “The Bells of Bicetre” analyses the effect of a stroke on a man in the prime of his life, who became a publisher of a highly influential Paris newspaper. Then suddenly he finds himself in a Paris hospital, speechless and paralyzed, yet surprisingly clear of mind. For the first time in his life he is forced to reflect. The book was published in 1965: it is odd to witness a so deep clairvoyance. Who was inspired by the reading of this book? Perhaps Bauby himself or Schnabel read it. Experts in narrative medicine are still debating and we, as in a movie of Akira Kurosawa, or as in a Pirandello’s play will probably never know the true facts.