Maria Giulia Marini (MGM), Director of Innovation in the Health Care Area of Fondazione ISTUD, and Enrica Leydi (EL), content manager of ‘Chronicle of Healthcare and Narrative Medicine’, interview professor Arthur Frank about the definitions and value of narrative medicine.

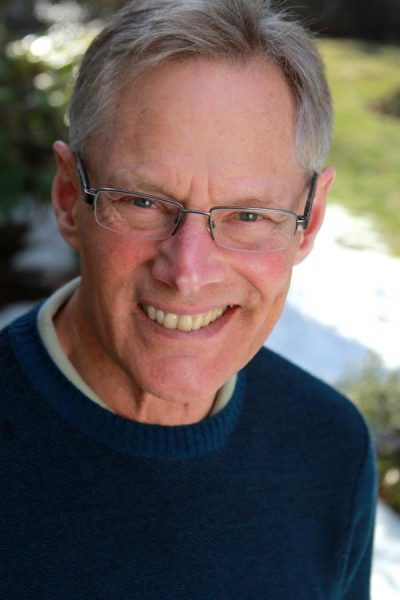

Arthur Frank (AF) is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Sociology, University of Calgary, and has been Professor II at VID Specialized University, Norway. He writes and lectures on illness experience, narrative, and ethics of care. He lives in Calgary, Alberta, Canada. He received his Ph.D. from Yale University in 1975; his M.A. in Communications from the University of Pennsylvania in 1970, and his B.A. in English from Princeton University in 1968.

He is the author of At the Will of the Body (1991), The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics (1995), The Renewal of Generosity: Illness, Medicine, and How to Live (2004), Letting Stories Breathe: A Socio-Narratology (2010).

His new book, King Lear: Shakespeare’s Dark Consolations (2022), proposes vulnerable reading: how people living vulnerable lives can find resources in the language, the characters, and the story of King Lear. He presents the vulnerable reader as a complementary figure to the wounded storyteller, shifting attention to where people learn the stories that are resources for living their lives.

In this interview:

Narrative in medicine

EL: How did you approach narrative in medicine? Where, when, and how you discovered it?

AF: I encountered the principles of narrative medicine before Rita Charon had coined the term for it. For me it came out of two things: my medical sociology background and the years that I was ill, when I wrote my memoir At the will of the body. More specifically, my own illness experiences made two sets of differences crucial for me, and both are the context of my interest in narrative medicine.

One was that treatment is not necessarily care. There is a significant difference between treating the patient and caring for them. I felt the difference in the way healthcare professionals approached me, whether they were coming truly caring for me or just delivering treatments. It’s not a dichotomy, the two coexist with each other, but there is a difference and I developed that in my early writing.

The other difference is between cure and healing. In cancer care, cure is defined as a 5-year remission rate. That has very little to do with individual sense of healing. Organized medicine (in North America since the Flexner report and the reorganization of medical schools on a scientific model in the early 20th century) has a problem recognizing needs of healing; those get lost in financial pressures and more instrumental daily tasks.

So, my work has always been about how medicine as an institutional treatment system could help lessen the profound alienation that illness induces rather than intensify it. Especially in cancer care, many people feel that the way they were treated in healthcare institutions intensified their alienation rather than healing it.

MGM: You reminded me of PTSD. So, there are people who are cured but they still have PTSD.

AF: I think anybody who’s had a life-threatening illness experiences some level of PTSD. Although I wouldn’t use that language because PTSD it is being used so generically. In fact, the word trauma is one that I’ve tried to avoid because everything now is being called a trauma. It’s a kind of linguistic inflation.

MGM: There is something that I always say to my students: if the taking care is good, you can die healed. The healing goes much beyond the physical body. When there is a real understanding, when there is a real taking care, when there is real listening, when there is a real intimate relationship, one can solve the things which have been unresolved for their whole life. You can die, but you are healed.

AF: I think the work of Cicely Saunders and the hospice movement anticipates and resonates with the ideals of narrative medicine. It’s not inaccurate to say that the narrative medicine is trying to bring many of the practices of Hospice care as understood by Cicely Saunders into other forms of medical encounters. I used to joke: why do you have to be dying to get palliative care? Narrative medicine takes that question seriously.

MGM: It is true! You get good care when you’re in the birth unit, you are forgotten with your disease when you are an adult, and then you get good care when you are dying. Good care is just in the beginning and in the end. There’s poor care in the middle.

definition(S)

EL: Is an official definition of narrative medicine where you work? And what is narrative medicine for you? What is it in your daily practice, in your daily job?

AF: I mean the brief answer is I don’t work. I’ve been officially retired for about 10 years. All my work is short term contracts with universities.

As far as I know in Canada there’s no official definition of narrative medicine. I can see why institutionally such a definition would be useful in terms of claiming curricular space, funding, arguing for positions to be hired, but I would resist imposing boundaries around narrative medicine. I think it’s important to keep it open-ended.

To me, narrative medicine is the clinical application of humanities in medicine. It’s where humanities in medicine are focused on the clinical encounter between the clinician (be that physician, nurse, other form of therapist) and someone who, in that moment is a patient.

I’ve also always emphasized that being a patient is only a part, a small part, of being an ill person. The life of an ill person is far more encompassing. I find it seriously annoying when ill people are referred to as patients, as if as soon as you’re diagnosed with something, that is taken as your significant identity. It’s not. Being a patient refers only to those times when you are being attended by a clinical professional. And that it is a small part of your life.

My definition of narrative medicine is that it situates diseases in bodies and bodies in lives. Narrative medicine takes the extensive interest in people’s lives that other forms of clinical work often do not take. Specialist care wants to look only at the body part that is its specialty, whereas narrative medicine, in a cinematic term, pans back and looks at the at the larger picture. Narrative medicine believes that it needs to know about the life of the ill person, and it needs to speak to the life of the ill person. As John Launer said in the last EUNAMES meeting, “you ask before advising”. You need to know what’s already happening in someone’s life, and narrative medicine is the attitude of wanting to know. Narrative medicine calls on the clinician to progressively understand where the humanity of the patient lies, what it is about their lives that makes them interesting, and, in a great many cases, admirable.

The goal of narrative medicine is to enable people to know themselves in the process of becoming known by the clinician. My work in social psychology commits me to the position that we know ourselves by being known by others.

MGM: Is it like Paul Ricoeur and the self-acknowledgement?

AF: I think that idea is around long before Ricoeur, and in more dialogical form. The idea that we know ourselves in the reflective gaze of others goes back to the early 20th century: in North America, the work of the pragmatists, especially George Herbert Mead; in Europe, Mikhail Bakhtin. Among phenomenologists, it comes along later.

Tools

EL: So, would you agree with the statement that narrative medicine offers the tools to focus on the process and on the life of individuals in the clinic relationship?

AF: I agree with it generally. I know that institutional medical thinking and medical education likes the idea of tools. However, I hope narrative medicine would try to critique that language by asking what assumptions are embedded in speaking that way. Think about what tools implies as a metaphor.

The best philosopher of tools is Heidegger and his concept of equipment, which puts you in an instrumental relationship with things that then show up as objects of use, or what Heidegger calls equipment. That’s exactly the opposite for me of what narrative medicine tries to do. If you reduce narrative medicine to a set of tools, then you make the patient the object of the use of those tools. Tools determine your agenda, whereas a narrative approach not only allows but actively encourages the other person to set the agenda. As John Launer says, you only ask questions that come from the narrative that you’ve already elicited from the patient.

Humanities

EL: What is the history of medical humanities? How do you call them?

AF: The term “medical humanities” is prevalent in the UK, while in North America most people would refer to health humanities because non-physician clinical professionals feel excluded by the word “medical”. Health humanities is understood as a more inclusive term.

Right now, in the United States, inclusion and equity in healthcare are the dominant issues in health humanities. More and more colleagues are interested in how race, gender, and class affect access to care, quality of care, and treatment outcomes. In this sense I am kind of left behind because I’m still interested in dyadic clinical encounters. I’m still interested in what in The wounded storyteller calls the chaos narrative, and who doesn’t want to hear it.

Bioethics excludes the ways in which humans are self-divided. It wants the unified rational subject of ethical decision making, instead of understanding the human being as a radically self-divided creature with inadequate knowledge of itself. Institutional medicine is constantly trying to suppress and deny its endemic, conflictual relationships. Even though medicine is fraught with all manner of conflicts, it has very little institutional space to acknowledge these, much less to treat these as sources of productive change. Institutions tend to view conflict either as competition that can be channeled to increase productivity, or else as something to be eliminated. In neither case is it regarded as interesting and a source of change.

Instead, what the humanities can do, when working in clinical medical areas, is to open the recognition of what is systematically denied and excluded by official medical language. Years ago, the journal Health Affairs started a series called Narrative Matters, in which people were encouraged to write about health policy, beginning with a personal experience. A physician wrote an anonymous piece about various issues in the mental healthcare clinic that he was directing. I told him it was an excellent article, but that I regretted that he felt he had to publish it anonymously. He said to me: there are things that cannot be said in medicine.

For me, the fundamental task of humanities in medicine is to say those things. We are not physicians, we are not officially part of institutional medicine, so our task is to be able to say what people who are part of that institutional apparatus are unable to say. I haven’t drawn a paycheck from medical institutions and that’s given me an enormous degree of freedom, in terms of what I was able to say and look at critically.

Lastly, I think humanities have worked too hard to make themselves relevant to medicine. In the lectures I am currently preparing, I start off talking about medicine and then spend most of the time on Shakespeare, leaving the audience to develop the terms of relevance themselves. I’m addressing people who are living high stakes lives, vulnerable lives, as I call them. They have immediate and personal needs, and they need literature that can speak to what is chaotic, divided, and conflictual in their lives. Those are the lives I’m addressing by discussing King Lear in my book that’s just been published.

time

MGM: I try not to use the phrase “art therapy” often, for the same reasons that you find the word trauma inflated. Nowadays everything seems linked to therapy. I love, on the other hand, talking of art that inspires. We recently worked on The Tempest and non-violent communication. I’m not at easy with labels such as “therapy”, but unfortunately, we sometimes must use these words to negotiate with the counterpart, the doctors, and institutions. For example, when we use the word “disease” we mean something different from the how the doctors conceive disease. And the same happens with the word “body”.

AF: Yes, negotiations begin with reconciliation of different meanings.

MGM: In the previous EUNAMES meeting, the shortage of time at the medical visit came up as an issue. It was argued the possibility to apply narrative medicine during the visit. The problem is time. Is time too little or is it a matter of attitude and education?

AF: When I’m speaking to nurses and early career physicians, I encourage them to take two or three seconds and be silent with the person, before asking one or two curiosity-based questions. This way you begin to elicit a narrative of this person’s life. Maybe take one patient a day, when the schedule permits, and spend 10 minutes being curious about their life and how illness is figuring in that life. I advise starting with the smallest unit.

One thing I must be really honest about is that, especially since the COVID pandemic started, I haven’t been in hospitals. I used to be in hospitals quite often, sometimes being invited to shadow clinicians, but I haven’t had an opportunity to do that recently. I recognize that I’m out of touch with day-to-day clinical practice and I’m very aware that that practice has changed in the post COVID medical environment and that healthcare workers were traumatized by the workload and what happened. I think that usage of trauma is warranted, partly because healthcare workers’ distress is too often ignored, especially by governments.

Chaos and restitution narratives

MGM: Speaking of COVID, think of Bergamo, the city 60 kilometers from Milano where there was the highest mortality rate in Europe. I still remember the ambulances coming from there. We worked with Bergamo’s hospitals, making the doctors write “Illness Diaries” about what they saw and lived during those days and nights. We have been working a lot with them and we can say here the word trauma because they saw so much death. The problem was that there they were not even believed in Italy: the south didn’t believe that there was so much death in the north. It was very divisive… Now, we are still working with healthcare professionals in Bergamo and in Milan too, putting pictures on the walls to help people to let go because I know the pain is still there. I was really shocked by the chaos narrative in Bergamo…

Your Wounded storyteller is a milestone. Today, I wanted to speak with you about the restitution narrative and the reductionism of the biomedical model. So, with a group of life sciences students, we have been carrying out a project-work on health through history. We looked at the concept of health in relation to the value of life among the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, in the Middle Age, in the Renaissance, and up to the Industrial and contemporary age. It came out that there was almost nothing about life, but much on remedies, drugs, treatments, and things related to the biomedical model. My impression is that reductionism has always been there through the centuries. Therefore, we can say that humanity has always been entangled in a restitution narrative. Would you like to comment on that?

AF: Over time medicine has become increasingly effective at curing and it has had less and less time and financial interest in taking extensive interest in the life of the ill person.

Lewis Thomas, head of the Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York in the 70s, once wrote about being a medical resident in the 1930s before antibiotics. He explained they had a lot of time to spend with patients and acquire good bedside manner. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much they could do for them, treatment wise. As medicine becomes more and more technological, using that technology crowds out talking to patients about their lives.

Nowadays, the physician mediates the sale of goods and services between pharmaceutical companies, equipment providers, and the patient. In the United States the other big player in that mediation is insurance companies. That’s simpler in Canada, where you have a single third-party payer, but it’s still very much a factor.

So, you’re right: these things were there before. The question is when do you have threshold moments? I would argue that such moments include the development of antibiotics at the end of World War Two, and later, in the 1950s and 60s, the end of the house call, when physicians no longer routinely went to their patients’ homes.

Soon after the time when physicians quit going into people’s homes, they invented the professional category of family medicine. You could cynically argue that that was a kind of compensatory mechanism. Here we get at what narrative medicine needs to take back. In earlier days, physicians actually saw patients where they lived their lives. Now the patient appears already gowned in a stripped-down examination room, and the physician’s gaze is directed immediately toward the symptomatic or treatment area of the body.

In the last 10 years there has also been the intrusion of the computer into the consultation room. In North America, particularly in the United States, the medical encounter is heavily scripted in prompts on a screen, and time regimented by the screen. The physician has little time to complete a task before the screen alerts them that they are not moving fast enough. It turns the patient into the product of reimbursable time. But where this is happening remains widely distributed. That takes us back to what narrative medicine seeks to resist.