Could the institutions offer assistance, care and quality of life to ill people?

Or is the role of caregivers, today silent and invisible people, non-replaceable?

“If caregivers do not really exist?” is the title of the report of the “I have the right to…” campaign, realized by Cittadinanzattiva Emilia-Romagna in 2020 to advocate for more rights, more health protection and a better quality of life for caregivers. The campaign started in November 2019 and ended in February 2020 before the Covid-19 lockdown; 200 caregivers have participated by sending their stories

The report is enhanced by 10 podcasts on 10 rights denied to caregivers, chosen from the stories we collected.

The full report in Italian language, is available at https://www.cittadinanzattiva-er.it/e-se-i-caregiver…-fossero-davvero the podcasts at https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCoyeD6OJTsohNvPvMGlp3ig.

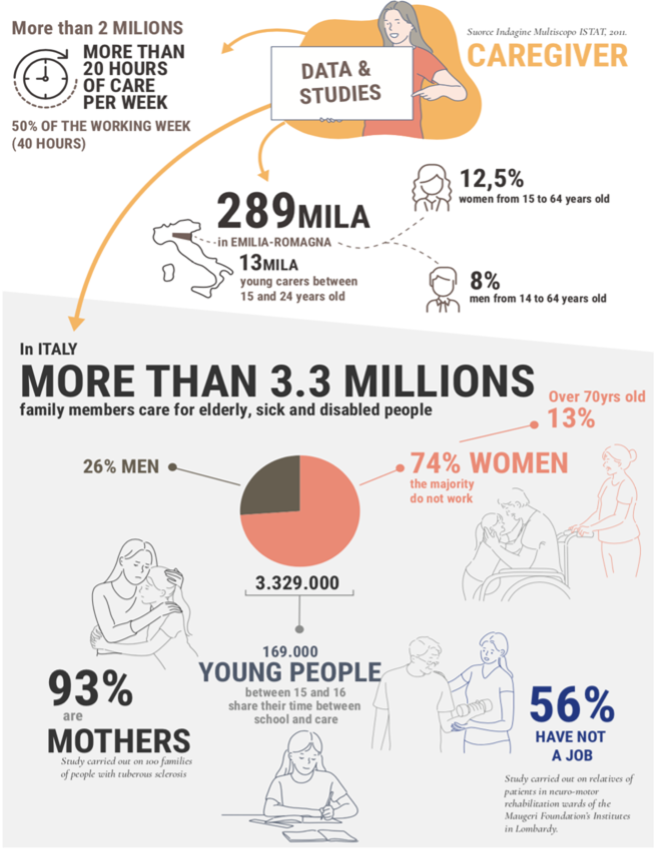

In Italy, a real army of invisible peopli supports the welfare system by caring for ill people: they are parents, partners, children, siblings, friends, neighbors who take care of a person without any remuneration. Caregivers cope with the huge burden of long term care for people with disabilities, chronic or degenerative and rare diseases. At different stages of the disease, they perform different tasks: they collaborate in the assistance during hospitalization, discuss with the doctors, deal with the various bureaucratic procedures, and take care of the family. They interact with the general practitioner and the social-health network and collaborate in daily nutrition, they help with personal hygiene, mobility and facilitate family and social relationships. Their role is strategic because it can impact on the person’s adaptation to the new condition of illness, promoting a better quality of life.

We also know from research that caregiving times range from a few years to more than 30 years. They care seven days a week and have no holidays. The everyday routine includes 4/6 hours of direct work and 10 hours of indirect work:

“Tell me if this is not a job: I cook, I wash, I iron, I prepare parties to ensure lightness at home. I look after my son, I take him to school, I accompany him to the doctor, I stay with him day and night during hospitalization, I am the one who attends doctor’s visits and schedules appointments, I prepare and give therapy every day, and I don’t mention the bureaucracy What about the sleepless nights? Or the days that are planned and cancelled because of unexpected events? They have no holidays, no hairdresser, no reading of books in peace, no tea with friends, no cinema. Tell me if this is not a job.”

From these fast-paced words, as the carer daily life is, we can understand the daily activities burden on different fronts, often in total isolation.

Young caregivers, who are involved in caring for people with complex care needs, require a special attention. Schools are the first place where problems can be identified and drop-out avoided. In order to prevent drop-out, it is essential to increase awareness among teachers and school staff about young carers needs, to involve their peers, to create networks and campaigns to prevent the risk of loneliness, stigma and social exclusion.

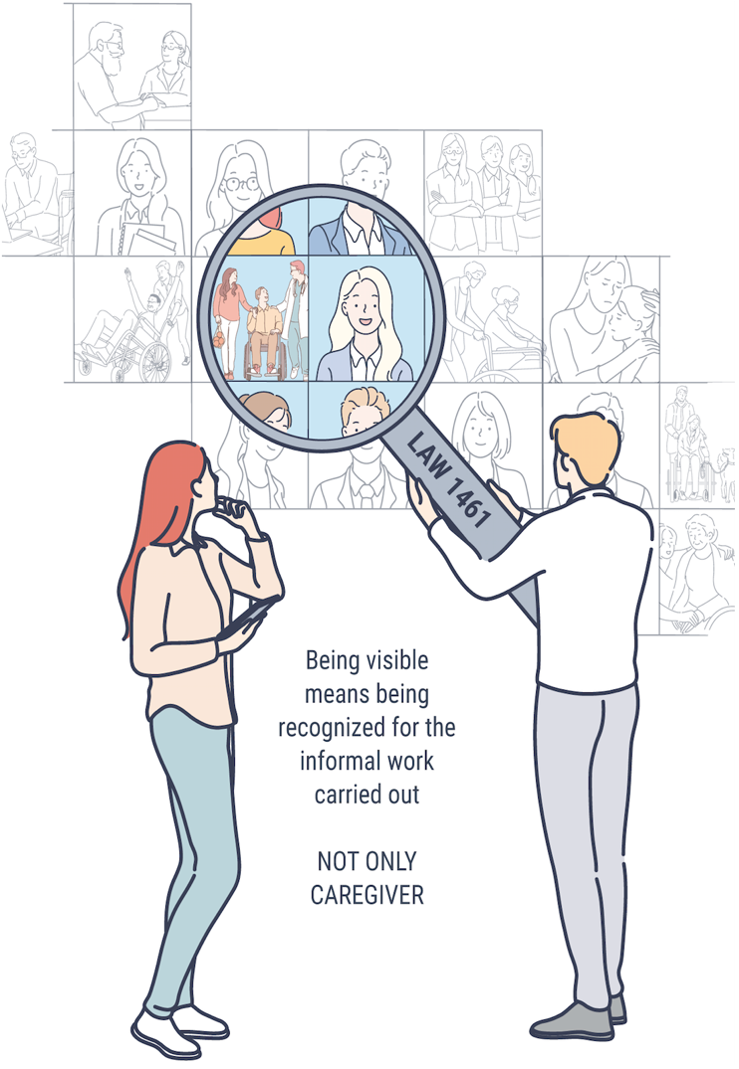

Caregivers have been waiting for years for a law to be approved and it was only in 2019 that National Law 1461 ” Measures for the recognition and support of family caregivers” was presented to recognize their rights.

A step forward in this direction has been made by the Emilia-Romagna Region when in 2014 adopted a law regarding family caregivers: ” Provisions for the recognition and support of the family caregiver (person who voluntarily provides care and assistance)” and instituted the Caregiver day, but this is not enough in terms of rights.

This regional law, although it does not have any consequences on the social rights of caregivers which are nationally regulated, nevertheless aims to enhance and improve the lives of citizens, both cared and carers, by recognizing a social role for the latter.

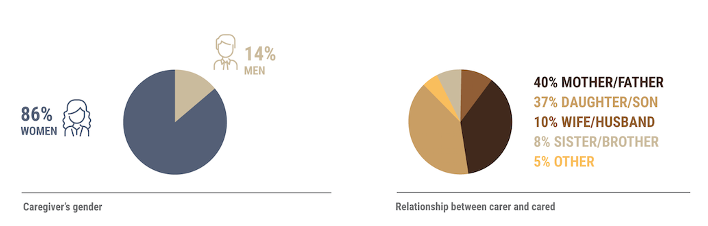

Caregivers who responded to the Cittadinanzattiva campaign

Most of the participants in our survey are women, 86%, with implications that are sometimes penalizing in terms of job for those who are workers, but also in terms of overall family management. The few men who shared their stories, 14%, take care of a wife, a child or elderly parent.

“If you think that the carer is only a woman, it is not so. I am a man and have been caring for my wife for 20 years.Pain, understanding, sensitivity and love are also emotions that we men experience”

They cope with many fights, such as the slowness and the fragmented responses of the social-health system, the bureaucracy, the physical and cultural barriers, and this happens in total isolation without an accompanying person.

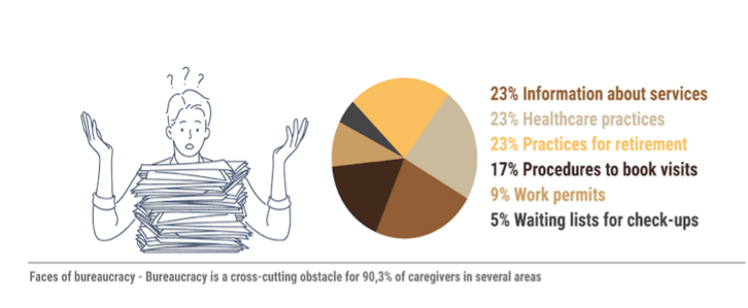

For 90.8% of caregivers, bureaucracy is “a mountain on their shoulders”: it represents an obstacle in the different areas in which they are interact. “In my long experience as a caregiver, I have met attentive and sensible professionals, but sometimes I have met unintelligible situations, which have led me to think: ” why can’t I sit at the same desk where they write the rules that involve people like my son, to make them understand that they are creating complications for everyone?”

Rather than economic support, they ask for services and information (64% Assistance in everyday life 25% Information 11% Training).

“I would have the right to receive proper information and guidance on the practices to be followed, especially for social security purposes; I am aged and cannot keep up with the evolution of technology, I often lose relevant information that should also be provided in the traditional way (on paper and by ordinary mail).

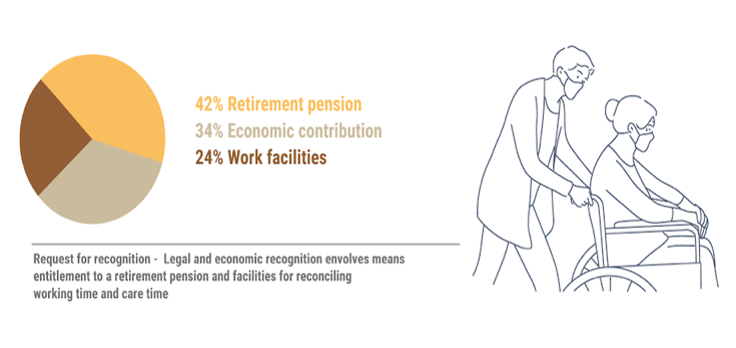

Legal and economic recognition of caring means legitimacy of pension rights and facilities to reconcile work time and care time (42% pension, 34% economic contribution, 24% benefits for employment:“As a mother of a disabled person, for 30 years I have spent my life caring for my daughter without any recognition and now I find myself unable to deal with helping her in 24 hours’”

28.5% of caregivers ask for quality of life/wellbeing: “Time spent with my cared is lighter if I have time for myself”.

15.4% simply ask for the application of laws in force, such as the National Chronicity Policy Plan.

As far as regards the future, 14.1% of carers are warrying about it because they are getting older: “I would like my son to end his life a little earlier than me so that I can also close my eyes in peace”.

0.8 % of young carers are afraid of not having future: “I often look other and ask myself will I have these chances? Then I look at my room out of the window and watch people walking, talking, embracing each and hear familiar sounds and I realise that this is my life for now. I am not really happy, but I know that I am important in my mother’s life”.

0.4% of young carers ask to be treated the same as working students.

Unfortunately the process of approving the law 1461 has come to a standstill.

Caregivers say that “Being visible means being recognized for the informal work they do, having a network of services able to support them in their daily care, seeing the elimination of many bureaucratic obstacles against which they currently have to fight and which represent an additional burden in addition to the care . Being visible also means being considered as a citizen, mother, father, sister, child, etc., not just as a caregiver. Being visible means having a law to protect them. Without any recognition of their role, they will remain invisible”.

The responsibility that characterises carers in the fulfilment of their role also belongs to associations and citizens who support them in their fight for legal recognition of their rights.

Thanks to the “I have the right to…” campaign, 100% of caregivers are advocating for the approval of Law 1461 by reporting difficulties and dysfunctions they face in their daily lives. So their voice has been more clearly heard, with a twofold outcome: making caregivers feel less alone and increasing the awareness of their needs in the community.Grazie anche alla campagna di Cittadinanzattiva Emilia-Romagna il 100% dei caregiver chiede di approvare la legge 1461 e segnala le difficoltà e le disfunzioni con cui deve fare i conti nella quotidianità. La loro voce si è sentita più forte con un duplice risultato: di far sentire meno soli i caregiver e di elevare il livello di sensibilità verso le loro istanze nel complesso della cittadinanza.

Rossana Di Renzo lives and works in Bologna. Former coordinator of health placements and AIUSL contact person for University relations, her interest has always been narrative and applied narrative medicine which she uses in training courses for health professionals, in the degree course in Nursing at the University of Bologna and in research. Nowadays she is the responsible of the regional coordination of the Associations of chronic and rare patients network of Cittadinanzattiva E.R. and she collaborates to introduce narrative medicine for research activities with Associations of people with chronic and rare diseases. Contact ross.direnzo@gmail.com

Marilena Vimercati lives and works in Milan. Former teacher of sociology she collaborates with ISMU—Initiatives and Studies on Multiethnicity, an independent scientific body—to carry out projects focusing on interaction between migration processes and training paths for professionals.She has been using narrative methodologies in the contexts she has been working (with students, health professionals, also in the framework of European Projects) and today she continues to use them with migrants. In recent years, she has also collaborated with Cittadinanzattiva Emilia Romagna on research projects using narrative medicine with associations of people with disabilities, chronic and rare diseases. Contact mvimercati75@gmail.com