Donatella Lippi (Florence, 1959), graduated in Classical Literature, with specializations in Archaeology, Archivistics, History of Medicine, Bioethics, is Professor of History of Medicine at the School of Human Health Sciences, University of Florence.

This year he published for Angelo Pontecorboli Editore the volume Dante tra Ipocràte e Galieno. Il lessico della medicina nella Commedia. The preface is by Giovanna Frosini, Academica della Crusca and Full Professor at the Department of Humanistic Studies of the University for Foreigners of Siena. A fundamental contribution was also made by Chiara Murru, research fellow at the same Department of Teaching, who compiled the lexicographic entries in the appendix.

We interviewed Professor Lippi and Professor Frosini about Dante’s contribution to the vernacular language of medicine and what was the relationship of our poet with this discipline.

THIS YEAR WAS PUBLISHED YOUR BOOK DANTE TRA IPOCRÀTE E GALIENO. THE LEXICON OF MEDICINE IN COMEDY. WOULD YOU LIKE TO TELL US HOW THIS RESEARCH AND THIS INTEREST CAME ABOUT?

A few years ago, the School of Human Health Sciences promoted a meeting entitled “Un medico all’Inferno” (A Doctor in Hell): a provocative title that was not easy to understand and that, in fact, could give rise to several interpretations. In the intentions of the organizers, the aim was to allude to the historical-medical analysis of some passages of the Comedy, in order to create an opportunity to recover the humanistic dimension in the training of young doctors, within the course of History of Medicine. The title aroused curiosity and a smile, sparking off a rich series of comments, as it seemed to allude to the daily practice of the profession or the experience of the sick, in an almost journalistic sensationalism. In reality, the meeting foresaw the analysis of some passages of the Comedy, referable to the world of medicine, interspersed with the recitation of the most famous or suggestive ones, thanks also to the intervention of Riccardo Pratesi, a lover of Dante and of the Comedy, which he knows entirely by heart and of which he is a fine and aware speaker. Climax of the meeting, the exhibition of a skull of the Anatomical Museum, while the most painful verses of the Comedy were declaimed, those of the XXXIII canto, dedicated to Count Ugolino. The meeting was an extraordinary success and, on that occasion, a video was also made, accessible at the site of Vincenzo Natile, who was the skilled creator.

A few years later, but, above all, on the eighteenth anniversary of the death of Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), I decided to recover the warp of that meeting, transforming it into this text, which has absolutely no claim to completeness or absolute scientificity, but which wants to be a way to give material consistency to the figure of Dante and the medical culture of his time, a cue to deepen some aspects, which can then be analyzed in more detail in other places.

Compared to the years 2009-2011, in which I published an edition of the Commedia with historical-medical notes (Mattioli 1885, Fidenza), many works have been published by literary or medical experts, who have identified in the verses of the three Canticles references to precise pathologies and even to morbid conditions from which Dante himself would have suffered, but which remain specialized works, precluded to the general public and, above all, far from the world of students, who, instead, can find in the verses of the Commedia propitious occasions to feel Dante closer.

If this text, inevitably susceptible to extensions and in-depth studies, succeeds in igniting a debate and raising some constructive criticism, the objective will have been achieved.

Particular merit goes to the Publisher Angelo Pontecorboli, who has accepted the proposal of publication.

DANTE WAS A MEMBER OF THE ORDER OF PHYSICIANS AND APOTHECARIES, BUT WHAT WAS HIS ACTUAL MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE? AND WHERE CAN WE FIND TRACES OF IT IN THE COMEDY?

Was Dante a doctor? This was the title of a series of contributions, published in the British Medical Journal starting in February 1910 (BMJ 5, 1910, pp. 331-333), aimed at answering this age-old question. Muzio Pazzi, librarian of the Surgical Medical Society of Bologna, had responded in the Bullettino delle Scienze Mediche (vol. X, p. 352):

“Given the encyclopedic value of our greatest poet, it is no wonder that in the midst of the myriad of commentators swarming around the base of the superb monument of Dante’s work, like swarms of industrious ants at the foot of gigantic towers, or the walls of China, neither are doctors counted, literati and amateurs of chronicles enraptured by Dante’s profound knowledge of the ars medica, as well as of theology, philosophy and jurisprudence, nor that the same are tempted to discover whether the author of the unsurpassed and unsurpassable national poem had studied medicine.”

Where Dante had acquired this preparation is a vexata quaestio: medicine and philosophy, in the late Middle Ages, had many points of tangency.

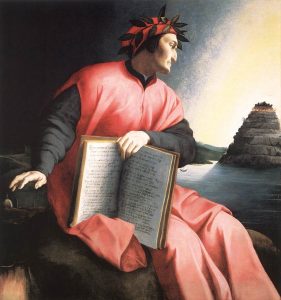

- Dante was enrolled in the Guild of Physicians and Apothecaries and could wear the long and wide red robe (lucco), adorned with white vaio, with the head covered by a hood (becchetto) with the tips falling to the sides of the face, typical clothing of the doctor: this is how he is portrayed among the blessed, in the Last Judgment painted in the Bargello palace in Florence, prototype of all subsequent representations. Raffaele Ciasca writes: “Alighieri, if he didn’t want to cut off the possibility to run the public honours, had only to choose among the seven major arts, the only ones that were surely kept in power, from the defeat of the magnate element onwards. He held the merchants of cloth and silk in contempt, he considered the wool merchants and furriers to be vile, and not having the money and the inclination to do, like his father, the money changer, he found himself at the crossroads between the art of doctors and that of judges who represented the aristocracy of the intellect, antithetical, in a certain sense, to that of the captains of industry and the bank …”. As for the choice of the Art, “they gave him the right of citizenship his philosophical preparation, his culture in medicine and in that complex of liberal arts that were then the foundation of philosophy as well as medicine.

- It is said that he had attended the lessons of Taddeo Alderotti in Bologna, whose students were Fiduccio de’ Milotti, who moved to Ravenna in 1300, and Mondino de’ Liuzzi, both Tuscans: when Dante reached the Court of Ravenna, Fiduccio became his personal doctor and assisted him until his death;

- Between 1304 and 1306, Dante was in Padua, where he frequented various doctors, among whom, probably, Pietro d’Abano (1250 c. – 1315 c.), interpreter of a new culture cultivated with the contribution of the Greek-Arabic science, assimilated through the direct approach to the sources, destined to be subjected several times to the court of the Inquisition.

- Even in Verona he was in close contact with various doctors, first of all the reader of medicine Antonio Pelacani (1275-1327), doctor of Matteo I Visconti, accused of heresy and necromancy, to which, perhaps, alludes in the Quaestio de aqua et terra.

- Dante loved Beatrice Portinari, whose father, Folco di Ricovero, founded the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova and whose housekeeper, Monna Tessa, was the first Oblate.

But, beyond these hints, which highlight particular formative circumstances and certain biographical elements, it is his work that offers the most evident evidence of his relationship with the world of medicine and health. More or less direct evidence, more or less marked references, compose a warp on which it is possible to reconstruct the body of knowledge of the poet, which substantiate the Comedy of concreteness and immanence. The points are countless: some are more direct, others only allusive: I am thinking of Inf. IV, 130 and following, where Dante mentions the Greats of Medicine; of Inf. XXVIII, 22-33, where the punishment of schismatics evokes an anatomical dissection; of Inf., XX, 52-55, with the soothsayers who have their faces turned backwards…

DANTE IS A MASTER OF COMPASSION AND EMPATHY. IT IS PRECISELY THESE VIRTUES THAT ALLOW HIM NOT TO CONFUSE THE SIN WITH THE SINNER, BUT TO RECOGNIZE UNDER THE OBSERVATION OF VICE THE GREATNESS OF MAN WHEN IT EXISTS. HOW CAN THIS TEACHING BE TRANSLATED INTO CONTEMPORARY MEDICAL PRACTICE?

The feeling of compassion evokes the sense of mercy, of closeness to the miserable. From late Latinity through the Christian Middle Ages, the works of mercy, expressed in the Gospel of Matthew, come down to our days and, although, from the time of Dante to today, the social context has changed profoundly and the sense of those moral categories must be declined in renewed behavior, the sense of participation in the problems of our neighbor is an important point of reflection.

It was precisely at the time of Dante that the work of the Confraternity of Mercy, whose name also recalls those values of evangelical charity, began.

When Dante announces to himself exile, suffering, solitude, nostalgia… he is aware of this condition, he is experiencing it and, for this reason, he is able to share it so effectively.

Herein also lies the lesson of the Poet.

If I transfer this circumstance to the world of medicine and health care, I cannot fail to recall what the philosopher Hans Georg Gadamer wrote: what medicine needs, in order to be more humane, is the figure of a “wounded healer”, a doctor who is not only respectful of the subjectivity of the sick person, but also inwardly aware of the weight of suffering and pain. A doctor, Gadamer says, must not only be a technician of pathology, but a person capable of understanding that beyond roles, something deeper binds his condition to that of the sick person.

“Here, alongside the demiurgic aspect of knowledge and art, emerges the pain contained in the common human matrix, bodily and mortal, which unites, beyond roles, doctor and patient…. A doctor “without a wound” cannot activate the healing factor in the patient and the situation that is created is sadly known: “on one side stands the healthy and strong doctor, on the other the patient, sick and weak”.

(Introduction to the essay “Where Health Lurks” by H. G. Gadamer)

DID THE PLAY HAVE AN INFLUENCE ON LATER MEDICINE? AND ON MEDICAL LANGUAGE?

The Commedia represents an essential moment in the history of the Italian language: in fact, it is no exaggeration to say, with a great scholar of medieval language and literature, Ignazio Baldelli, that Dante is Italian. No other author, in the course of the centuries-long history of our language, has had a role comparable to Dante, and, as Bruno Migliorini wrote, his importance can never be overestimated. The “Dante function” does not consist so much in the words that Dante invented, exploiting the mechanisms of the structures of the vernacular language, such as trasumanare (verb parasintetico, from umano > umanare + prefix), words that are, moreover, extraordinary, and that communicate a creative effort never again equaled by anyone, but in the fact that Dante used in the Comedy a very high number of words that had not previously had literary consecration, that now come out of the shadows of the only spoken use, and become for us traceable, documentable, recognizable. With Dante, Italian is recognized as such. Moreover, the great novelty of the poem is the enlargement of the poetabile, that is, the fact that in the Commedia every subject is treated, and the language is stretched, it extends, it becomes multiform and flexible: in short, a new language for a scandalously new work, which gives background to the description of the whole universe. No subject escapes Dante: from the lowest to the highest, in an extraordinary variety of registers and mixture of styles that no one will be able to replicate. With Dante, the vernacular language becomes capable of describing reality, of giving voice, sound and form to all events and all feelings. In this sense, the Commedia certainly had an influence on the language of medicine, as it did on the language of any other sector of the Italian lexicon: I would like to recall just a few examples, taken from the lexicographic tables prepared with great accuracy and finesse for this volume by Chiara Murru. See therefore: epa ‘liver’, used several times in the Inferno, which survives mainly through the derivative adjective hepatico, or the compound noun hepatitis; feto, Latinism, is Dante’s first attestation, and recurs in Stazio’s discourse in Purgatorio XXV 68 on the generation of the human soul; nape ‘spinal cord of the neck region’, a word of Arabic origin (Arabic wisdom was of extraordinary importance in medieval medical science, as Avicenna absolutely testifies), which recurs in the scene of Count Ugolino’s horrendous meal with the head of his eternal enemy, Archbishop Ruggieri, and serves as a tragic counterpoint to the death by starvation inflicted on the count and his children; pulse, meaning ‘the artery’: so in the expression “the veins and the wrists”, one of those idioms that from the verses of the Comedy have almost insensibly transited into Italian and still survive in common usage, with paradigmatic or proverbial value (even in the mispronunciation “the veins of the wrists”); omore ‘mood’, which recurs in the terminologically very precise description of Master Adam’s dropsy: but the whole episode of Inferno XXX, culminating in the clash between Master Adam and Sinon, is an extraordinary treatise on medicine, as the chapter devoted to it by Donatella Lippi shows very well.

More generally, then, Dante’s great attention to Latinisms counts, because Latinity represents a formidable and inexhaustible deposit, through which to enrich the vernacular; there are many first-hand Latinisms, also relating to the sciences, that Dante draws from the classical lexicon and adapts to the structures of the new language: even here it is not only aulic words, such as tetragon, but also common words such as fertile, of application also medical; it is already more specific complexion (‘composite physical structure of every earthly being, determined by the composition of various elements’), from the Latin. complexio, which appears in the Convivio and only once in the Commedia (Paradiso VII 140).

THE EXPRESSION OF COMPASSION PASSES THROUGH LANGUAGE AND COMMUNICATION: WHAT ASPECTS OF DANTE’S DIALOGUES, IN YOUR OPINION, CAN PROVIDE A USEFUL MODEL FOR TEACHING/LEARNING A LANGUAGE THAT CURES?

It has been repeatedly observed by scholars that a great novelty of the Commedia is precisely its dialogical construction; it is Dante’s dialogue with the souls that gives life and substance to the story of the journey to the afterlife, which for the first time acquires in this way a narrative character, a story told. The great episodes of the Comedy that we all have in mind, and that constitute – a very important thing – a common heritage of images, concepts, feelings, arise from great dialogues: Francesca and Paolo, Ulysses, Count Ugolino, Manfredi, Buonconte, Beatrice, Cacciaguida … we can enumerate many of them, because this is the Comedy, a great dialogue between Dante and souls, between Dante and Virgil, Dante and Beatrice. The dialogue has a properly educational function: Virgil instructs Dante by dialoguing with him, he shows him the way, he saves him from the dangers of Hell, he shows him the gentler ascent to the shores of Purgatory; to Virgil Dante manifests his fears, his doubts, his hesitations, his requests for knowledge. To Virgil Dante asks how the Inferno is made, from Virgil Dante takes his leave on the top of Purgatory after a very sweet goodbye. When Beatrice reappears on the scene, in canto XXX of the Purgatory, she addresses to Dante a harsh reprimand, which, this time, will leave the poet a few syllables for the answer that will confess his betrayal on earth and his repentance in the “divine forest thick and alive”. In the sky of Mars, the conversation with the ancestor Cacciaguida, as desired as Aeneas’s meeting with Anchises, because it represents the vindication of one’s own history and dignity, will be opened by solemnly Latin verses, and will conclude with Dante’s decisive question about the meaning of the journey and especially of the story of the journey, that is, of the Commedia itself.

But the conversation is also highly therapeutic for Dante: not only in his relationship as a disciple with Virgil, in Inferno and Purgatorio, as a student with Beatrice, the beloved maiden who now becomes the teacher who introduces him to the mysteries of Paradise; but also because through the encounter and dialogue with the souls Dante (re)thinks about himself, his own history, his own journey as a man and a poet, he remembers, relives, and even changes profoundly with respect to the past. Dante heals his soul by dialoguing with those he has loved on earth, with those he has admired while he was alive, with those he has had to mourn because of an early separation, and now he finds them saved, with joy. In this sense, it is above all the dialogues of Purgatory that teach Dante the sweetness of remembrance, the relief of recognition: because Purgatory is the canticle of rebirth, of certain hope, the canticle in which the condition of the wandering and penitent souls is the very condition of Dante, and of every Christian. It is not for nothing that it is the canticle of friends, artists, illuminators and poets, the canticle that gives us back what is properly, powerfully human.

So Dante trembles with joy for having found Casella again on the beach of the Antipurgatorio, and asks him to resume the ancient custom of setting to music the poems he wrote; and he is comforted in finding Forese again among the gluttons, the friend of his youth, the brother of Piccarda, but also of Corso Donati: with him they had exchanged verses of harsh realism, full of insults: but now, on the frame of the Purgatorio, one can make amends for the past, and heal those insulting exchanges. And in front of Buonconte di Montefeltro, the valiant enemy who died and disappeared in the fierce battle of Campaldino, all political opposition is overcome, and Dante only wants to know what happened to his body on that bloodstained Saturday. Buonconte’s words show his attention towards the pilgrim, the unusual pilgrim who is alive, and express his nostalgia for that lost body, his sense of the end, his serene reliance on God’s will. Like Buonconte, like Manfredi, the young Swabian prince, son of Frederick II, blond and handsome, but disfigured by mortal wounds, all the souls in Purgatory, who recognize in Dante a brother on the path to salvation, speak to him with words of gentleness, care, attention; and these feelings are expressed above all by Pia, not by chance a woman, who desires rest for Dante, even before the memory of herself: it is these words of kindness, of delicacy, of caring, of sharing, that cure and heal body and soul.