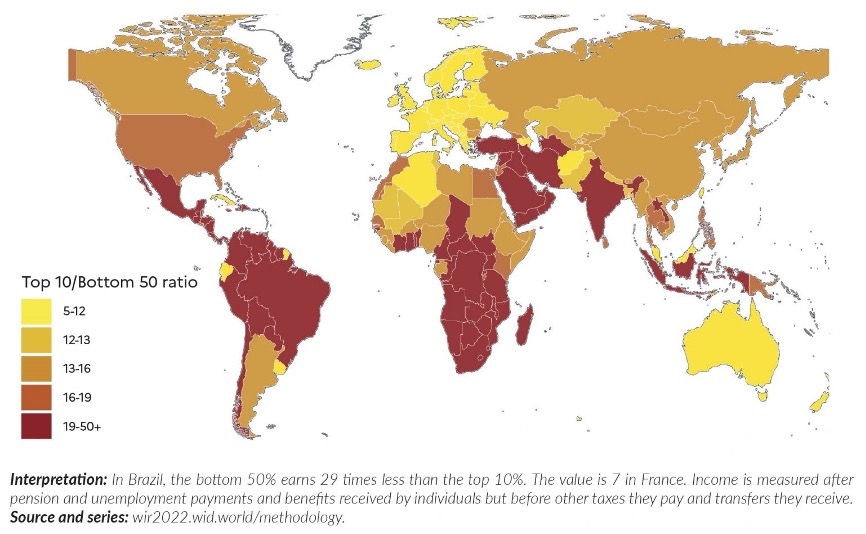

Our contemporary age is a period in which human beings, with incredible acceleration, have produced and are continually bringing about a technological revolution that has had a frightening impact: to the detriment of the well-being of a few – facts 10% of the total population on earth holds 75% of the wealth, we have a population that is very difficult to feed and give health and hospitality to on earth (over 8 billions inhabitants as of November 2022 compared to the population of 1 and 7 billion estimated in 1910), and damage, most likely irreversible to our planet caused by global warming resulting in desertification and inability to exploit the land to derive food.

The historical era of the Anthropocene: anthropos at the center, not as the crossroads of art and science, as seen in humanism, but in the worst sense with a social system that destroys the planet and creates inequities in the distribution of wealth; the “magnificent progressive fortunes,” caustically described by Leopardi admitted the truth of the Machiavellian limitation “‘Ipse faber fortune suae,’ each is the maker of his own fortune.”

The individual and cruel selfishness of the success and well-being of the few no longer justifies the drama of the many. We can say that neuroscientist Iain Mc Gil-Christ is sadly right when he states that we are slaves to our left hemisphere of the brain, we wished it could have been only the logical and rational one-and instead it is the one of greed and short-term vision, having possibly betrayed our right hemisphere, the one of humanism, art and science as intuition, and empathy with others. In short, we have left humanities and humanism, at least apparently, by the large demographic numbers and indicators of well-being or malaise.

Let us start to reanalyse around the last hundred and twenty years from the Industrial Revolution and Freud, and the discovery of the unconscious. Parallel to the evolution of scientific and technological discoveries, Freud hypothesizes, based on empirical cases, how our mind is made and discovers its “monstrous side,” not so much identified in the ES, that pleasure principle that brings us back to the lost state of nature, but in the loss of the reality principle, the Ego, and especially in the Superego, which creates the disturbed neurotic, potentially degenerating into psychosis.

The Physician Sigmund Freud operates in Vienna in the late 1800s and early 1900s, in a very restrictive environment yet also determined by subterranean forces, such as those on sexuality, that want to come out of the closet- I would say remove the white and golden Habsburg stucco -along with the many inner conflicts, the many faces of the human being.

Next to the joy of life of the ES, Freud with the Superego, in his masterful book, The Discomfort of Civilization gives in advance an explanation of what will happen and what generally happens in hyper-hierarchical civilizations where people’s faculty of thought is taken away: as an example, it will be precisely that hypertrophic Superego who will “trivially”-I borrow Hannah Arendt’s title, The Banality of Evil (3)-execute the orders to send six million Jews to the gas chambers, as reported by Nazi hierarchs in the Nuremberg trial. “We were carrying out the orders”: and Arendt comments in amazement, “But is it possible that they did not think? Didn’t they ask themselves ethical questions?” and the hierarchs replied, “An order is an order.”

And it is the superego of the norm, even the most terrible one, internalized to the point where guilt for what has been accomplished disappears. The ethics of the reality principle, “compassion,” “humanitas,” burned away by that totalitarianism and the other totalitarianisms of the 20th century.

One-Dimensional Man

While through vaccinations, the potabilization of water, the discovery of antibiotics, the creation of wealth in some countries extended life, genocide, and massacres were committed in others: the Armenians in 1912, the Great Leap Forward promoted by Mao between 1949 and 1976 that caused the extermination of 40 million dead, in China, the Holodomor (1932-1933) caused by Stalin in Ukraine, who then with his gulags and deportations suppressed some 30 million people, the futility of Vietnam, the wars in the Middle East, the Desaparecidos in Argentina and Chile, the Hutus and Tutsis in Rwanda to the genocide of the Serbs in Milosevic’s mass graves. Now we are facing another war, this time almost at home, or at least on our continent, in Europe between Russia and Ukraine.

It improves not only the technology of Health and Wellbeing but also the technology to produce Death. And so it was that Freud, who at the beginning of his studies had contemplated only the pleasure instinct, after World War I adds an instinct previously unpronounceable to humankind: the death instinct.

Alongside this, homo as Marcuse declared is kept in check only through consumption: the One-Dimensional Man is born, who takes far more than he gives to the planet, and throws away: enlightening and prescient is Calvin’s account, written in 1072 in his Invisible Cities, of a city, Leonia, that continues every day to consume to the bitter end: I see much in it of the existential condition of some affluent countries that then go and export their garbage outside, to other regions, because they do not know what to do with it.

The city of Leonia remakes itself every day: every morning the population wakes up amidst crisp sheets, washes themselves with soapsuds freshly peeled from their wrappers, wears shiny new robes, pulls out tin cans still intact from the most perfected refrigerator, listening to the latest nursery rhymes from the latest model of appliance. On the sidewalks, wrapped in terse plastic bags, the remains of yesterday’s Leonia await the garbage wagon. Not only the crushed tubes of toothpaste, electrocuted light bulbs, newspapers, containers, packaging materials, but also water heaters, encyclopaedias, pianos, porcelain services: rather than by the things of every day are manufactured sold bought, the opulence of Leonia is measured by the things that are thrown away every day to make way for new ones. So much so that one wonders if Leonia’s true passion is really as they say to enjoy new and different things, or not rather to expel, to remove from oneself, to cleanse oneself of a recurring impurity. What is certain is that garbage collectors are welcomed as angels, and their task of removing the re-statements of yesterday’s existence is surrounded by a silent respect, like a ritual that inspires devotion, or maybe just because once the stuff is thrown away no one wants to have to think about it anymore. Where the garbage collectors take their load every day no one wonders: outside the city, sure; but every year the city expands, and the garbage collectors have to stop farther away; the impressiveness of the throw away increases, and the piles rise, stratify, unfold over a wider perimeter.

Add that the more Leonia’s art excels at fabricating new materials, the more the garbage improves its substance, withstands time, weather, fermentation and combustion. It is a fortress of indestructible remnants that surrounds Leonia, towering over it on all sides like an acrochorus of mountains. The result is this: that the more Leonia expels stuff the more it accumulates; the scales of its past are welded into an armour that cannot be removed; renewing itself every day, the city retains all of itself in the only definitive form: that of yesterday’s garbage piling up on the garbage of the other day and years and lusters. The garbage of Leonia little by little would invade the world, if on the endless garbage heap were not pressing, beyond the extreme ridge, garbage heaps of other cities, which also repel away from themselves the mountains of garbage. Perhaps the whole world beyond Leonia’s borders is covered with craters of garbage, each with an uninterruptedly erupting metropolis at its centre. The borders between foreign and enemy cities are infected ramparts where the debris of one and the other propped up each other, overlapping, mingling. The more their height grows, the more the danger of-the landslides looms: all it takes is for a tin can, an old tire, a splintered flask to roll on Leonia’s side and an avalanche of mismatched shoes, calendars of years gone by, dried flowers will submerge the city in its own past that it vainly tried to repel, mixed with that of the other neighbouring cities, finally clean: a cataclysm will level the sordid mountain range, erase all traces of the metropolis always dressed up, will erase all traces of the metropolis always dressed up. Already from the neighbouring cities they are ready with steam rollers to level the ground, extend into the new territory, enlarge themselves, drive away the new filth.”

The one-dimensional man, the homo inhabitant of Leonia, who is making the earth an immense dustbin, subject to the plutocracy and thus to the tyranny (or totalitarianism?) of money and consumption responds to that homogenized Superego: well-being, consumption at all costs, or following the current locution, the “wow effect,” which burns overnight in the subjectivity of the human being, but impacts almost irreversibly in our planet. Yet this force has its diametrically opposite vector coexisting, the continuing demand for freedom (not liberalism), democracy, self-expression, self-creation, explicated in the great human rights being written right into the 20th century.

World Health Organization

After World War II, people, who had survived the horrors of both wars had, hoped to change the course of events, and they succeeded in part. In 1948, the year of the greatest ideals, the WHO World Health Organization, a body moreover founded precisely to deal with the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918.

WHO defines health as not merely the absence of disease but as entire biological psychological and social well-being.

Here we understand that it is not possible to separate health from well-being: health is wellbeing, and they are synonymous. So it is not enough to “save oneself,” to “survive,” in health from the Latin word “salvus,”, safe, for WHO health means “to exist well.” To the three bio- psycho and socio dimensions, a fourth dimension, the existential and spiritual dimension, has been added in the last forty years.

Not everyone in WHO agrees on adding spirituality to well-being since for many scholars this arises from the intertwining of the previous three dimensions but we feel we include it as an item in its own right, a treasure chest of values and attitudes that the person, or a group of people possess: do not necessarily fall back on or derive from revealed religions, but in a secular form of spirituality, which perhaps leads us to look for values even in the traditions of the past that might have had their own meaning: taking as much as giving, which the homo faber and one-dimensional homo has stopped doing. It takes far more than it gives to the ecosystem.