We are pleased to publish the project work of Piero Bottino, a geriatrician at the San Camillo Health Presidium in Turin and participant of the last edition of the Master in Applied Narrative Medicine of the Health and Health Area of Fondazione ISTUD.

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disease (second in frequency to Alzheimer’s disease) that affects about 1% of people over 60 and 4% over 85, with a slight prevalence of the male sex. It causes motor difficulties (stiffness, tremor, bradykinesia, falls…) and so-called non-motor disorders (constipation, dysphagia, dysphonia…) together with more or less cognitive severe deficits (memory, attention, concentration, etc.).

For many years, in the San Camillo Healthcare Presidium in Turin, where I work, there has been a rehabilitation service, structured as a Day Hospital, mainly dedicated to people with this pathology and their families. It is precisely the variety of symptoms the pathology can cause that requires a “multidisciplinary” rehabilitation approach, i.e. including various professionals able to respond to the different rehabilitation needs of patients. Our team includes physiotherapists, speech therapists, psychologists and neuropsychologists, nurses, occupational therapists, doctors, music therapists.

Since last March, due to the spread of the Sars-Cov-2 epidemic, all these treatments have been suddenly interrupted. This caused severe discomfort among patients, deprived of a precious resource for the maintenance of their activities and autonomy, and also among operators, aware that they were interrupting an important treatment service. Between many patients and us, over the years, a bond has been established, both professional and personal, of mutual knowledge and esteem. This has allowed the two physiotherapists who have been working with them for years to quickly organise rehabilitation sessions online, in a completely spontaneous way, using a simple and easy to use the platform from various devices. They sent an invitation to some patients to participate, and the group was formed in a few days. Informally, therefore, skipping bureaucratic procedures and technical obstacles, online rehabilitation has become a reality in our facility.

The group included 37 patients, who followed the sessions from home, on alternate days and at fixed hours. The success was resounding: a great many certificates of appreciation reached the therapists and the management. To assess more systematically the satisfaction and effectiveness of this type of treatment, the two physiotherapists drew up and administered a closed-answer questionnaire with an open space for final considerations to the participants.

This remarkable success gave me the idea of integrating the narratives into the questionnaire to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the service, analyse emotions, expectations and criticalities, comparing them, if possible, with the results of the questionnaire. With the help of ISTUD’s tutors in the context of the Master in Narrative Medicine, I elaborated a narrative trace, which was then sent to the participating patients, to obtain useful information consistent with the set purpose.

The response was good; 27 of them sent me their writings. On them, I tried to use the analysis tools learned in the master. I tried to create a word cloud to look for any recurring words; I analysed the presence of metaphors, the style of the various narratives, the strengths and weaknesses of the service.

Narratives opened a small window on the world of the people we care about, at least in part. They told us about their anxieties and their satisfaction in participating in these sessions, so different from usual. They gave us appreciations but also suggestions to improve the service and make it more useful and usable.

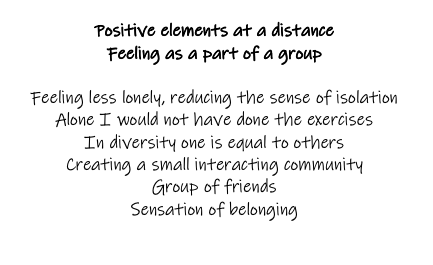

In the construction of the word cloud, after “physiotherapy, exercises, distance, activities, always, home” one of the terms that emerge most strongly is “group”. Much less frequent is the word “disease”. I was amazed by the concept of the group. I have always been sceptical about the possibility of carrying out rehabilitation activities at a distance, because I believe that physical contact, the relationship, the word, the look, are essential elements of the care relationship and that, through a video, all this is missing. On the other hand, the analysis of these narratives has shown me that even far away, at a distance, the group is born, grows and is structured. It emerges from the writings that the appointment, fixed and established, makes people feel less alone, creates equality in diversity, strengthens the sense of belonging.

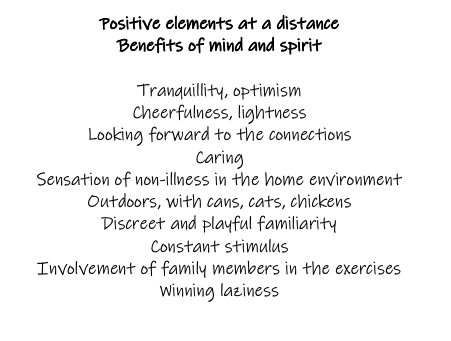

In the questionnaire, indeed, the area in which people describe having had the most significant benefits is that of mood, before specific physical improvements.

One of the elements that surprised me the most in the analysis of the narratives was the scarce importance, almost nothing, that is given to the benefits strictly linked to the pathology. Nearly all patients, in the most varied narrative styles, have shown psychological and relational benefits. Relatives and caregivers were positively involved; the domestic environment reduced the feeling of being ill; the punctuality of appointments was a constant spur to planned physical activity.

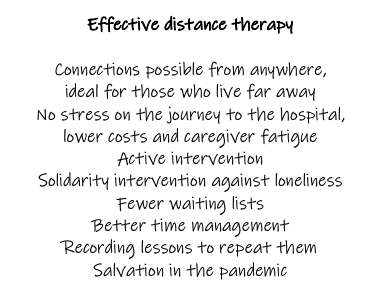

The study of narratives has also been a powerful means of analysing the effectiveness of the method. On the part of people who are often no longer young and have physical problems that are sometimes important, our perplexity about the usability of the technology has not been reflected in almost all the stories. Many have been self-sufficient in the use of mobile phones, PCs and tablets, others have benefited from familiar external help; all of them, in some way, were able to activate what was necessary. Narratives, on the other hand, have a significant educational effect on the use of technology. In an increasingly technological world, using these devices out of necessity has reduced resistance and fear and made possible what was thought to be too difficult.

The effectiveness of the therapies also emerges from the ease of use, which is possible in any place, without having to travel long distances to get to the clinics. Lower cost of transport, less fatigue of carers, less tiredness due to travel, all these elements are powerfully narrated and allow us to see these methods as a good help to our patients.

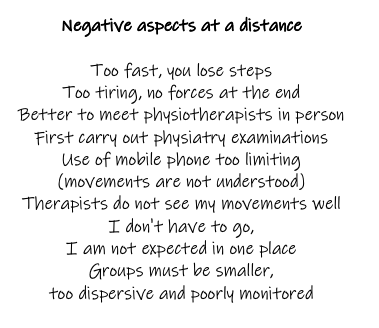

From the narrative, one can well derive what, on the other hand, does not work or is unwelcome. For example, the speed of the exercises proposed, the use of devices that are not very effective, with small screens, the group that is too large and dispersive, the impossibility of interacting directly, are essential elements to be grasped, not as criticism but as precious cues for improvement.

Indeed, the therapy in presence contains aspects that cannot be reproduced at a distance and, in my opinion, still essential for a good treatment relationship. The touch of the hands, the close attention to the gesture, the word of encouragement and correction are crucial, indispensable components.

The narratives allowed us to understand that a new way of “doing rehabilitation” is nevertheless possible, welcome and useful. But they have confirmed, once again, that in the fantastic world of caring, what is sought after is the relationship, being together, feeling cured.

The use of narratives, the opening of narrative space to those who want to tell themselves, is for me a formidable therapeutic tool. The healer who is willing to listen transmits a powerful message, makes the other person feel his desire to be useful to him, as a person before he is ill. In the technological world in which we are immersed, medicine also needs this new rebirth. The art of medicine, the art of healing, is no longer just the dutiful and correct application of algorithms. The relationship is not replaceable; it does not pass through calculations and numbers. The relationship allows for a “non-violent” comparison between the treating and the cured, between the medical world and the real world.

Narrative medicine, a new discipline centuries old and of wisdom, allows the rediscovery of this path. It requires attention, time and culture, but above all, it requires humility and patience. To cure is also to listen.

Time plays in our favour if we know how to use it well, even at the cost of further expenses.

Time is damned if pain saturates our day and prevents us from accepting our state.

Time is cursed if we don’t have someone to take care of us and not just physically.

Time flows relentlessly, alternating the hours of day and night and where, many times, it is not we who mark them, but our movements and our pains.– from a patient’s narrative