In this article:

- The ethimological Roots of old age

- The threshold of elderly today

- An encounter with Rita Levi Montalcini

the Ethimological Roots of old age

In Greek mythology, Geras (from here the words geriatrics, gerontology) was the god of old age. He was depicted as a tiny, shrivelled old man. Geras’s opposite was Hebe, a beautiful girl, the goddess of youth. Hebe was serving nectar and ambrosia to all gods and goddess on the Mount Olympus. Geras, on the contrary did not serve anything sweet, but, as the first meaning, the fear of becoming frail, old and to die.

His Roman equivalent was Senectus (from here the words senior and senatus). So if for the Greeks, Geras was a metaphor of disability (he is often depicted while leaning on a cane), for the pragmatic Latin approach, the being old gave access to wisdom, and as a consequence to political power in the Senatum.

However, Geras was not only considered as a source of frailty, but as the embodiment in humans of virtue: the more gēras a man acquired, the more kleos (fame) and arete (excellence and courage) he was considered to have.

In ancient Greek literature, the related word géras (γέρας) can also carry the meaning of influence, authority or power; especially that derived from fame, good looks and strength claimed through success in battle or contest. Such uses of this meaning can be found in Homer’s Odyssey, throughout where there is an evident concern of the various kings about the géras they will pass to their sons through their names. The concern is significant because kings at this time (such as Odysseus) are believed to have ruled by common consensus in recognition of their powerful influence, rather than hereditarily.

The Greek word γῆρας (gĕras) literally means “old age”: the status symbol of being old is acknowledged by the latin word antianus that means, more than the others, more dignity, more history: from here the word “ancient” , “ancienne” and in Italian “anziano”.

For the English word, old it comes from ald (Anglian), eald (West Saxon, Kentish) “antique, of ancient origin, belonging to antiquity, primeval; long in existence or use; near the end of the normal span of life; elder, mature, experienced,” from Proto-Germanic *althaz “grown up, adult”.

When we go through this analysis we learn that the culture who gave more ambivalent meanings to this word, Geras, is the Greek one: if on one hand, elderly could have been a status of wisdom, on the other it could also have been a realm of confusion, fear, and darkness, facing the liminality.

The threshold of elderly today

How do we measure the proportion of older people? Obviously, we have first to define what old means. United Nations defines older persons as those aged 60 year or over. On many occasions it is defined as 65+.

“Age 65 is generally set as the threshold of old age since it is at this period of life that the rates for sickness and death begin to show a marked increase over those of the earlier years”.

https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/events/pdf/expert/29/session1/EGM_25Feb2019_S1_SergeiScherbov.pdf

Suppose a man living in Western Europe is going to celebrate his 60th birthday. Is he old? Today this person would be considered middleaged, and around 93 percent of men survive until that age. About 150 year ago less then 25% were celebrating their 60th birthday. And indeed, at those times someone at age 60 was considered an old man.

The traditional age measure is a backward-looking one. It tells us how many years a person has already lived. But this is an incomplete measure because it ignores changes in life expectancy. Young and old are relative notions and their common reference point is life expectancy. Using the concept of perspective age, we may state that someone who is 60 today, may be in some respect equivalent to a person who was 43 years in 1850. A person who was 60 years old 150 years ago, may resemble someone who is 74 today.

Essentially, we recognized people as having two different ages: a chronological age, defined also as a “retrospective age”, that is a measure of how many years a person has already lived. Everyone of the same age has lived the same number of years. In contrast, prospective age is concerned about the future. Everyone with the same prospective age has the same expected remaining years of life. Population aging will certainly be the source of many challenges in the 21st century. Every year lived or expected is not only quantitative but also qualitative: if life expectancy before Covid was continuously increasing up to 2019, interesting is to assess the way old people lived these gained years: some studies show that although life is prolonged, the quality of the last years might be poor.

Public and private investment in medical research is primarily focused on reducing death rates, rather than reducing ageing and age-related disease.

“Even in the absence of disease and disability, human abilities—including memory, cognition, mobility, sight, hearing, taste and communication—decline with age), so that the quality of life for someone older than 90 years is on average very poor-. Given the increasing prevalence of multiple diseases, disabilities, dementias and dysfunctions at high age, it is not obvious that just extending lifespan beyond 90 years of age is a worthwhile undertaking.”

Living too long, The current focus of medical research on increasing the quantity, rather than the quality, of life is damaging our health and harming the economy, Guy C Brown, EMBO Reports (2015) 16: 137-14.

I know, maybe we are shocked reading the lines above, and here we have definitely trespassed the concept of ageism, and the more we go through this topic the more we might think what narrative medicine is for. It is to get out not from the standardized biomedical model but also from social cliché, to reach the biological, social psychological and existential model.

an encounter with rita levi montalcini

In 1999 I met Rita Levi Montalcini, Italian Nobel Prize for Medicine on her research on Nervous Growth Factor: she was only ninety at her age, and she died at 103 years; in 1999 she was asked to give a lecture talking about the “Future of health care”. She walked through the congress hall with the cane, and then, with no slide but “her stream of consciousness” a free speech lasting thirty minutes.

The silence of the audience was stunning: everyone was fascinated by her charisma, her inspirational words devoted to research and health care professionals: she never lost herself in the speech, she was stunning. Well, one could argue, she had the tools, she was a Nobel prize. I think that what she did is that she accepted with no shame the walking with a cane, the hearing aid, the glasses, therefore the “body aging”: however her soul and mind were so great, she was the living proof of the reasons why she won the prize, on neuroplasticity. Is it easy to come at this age as professor Rita Montalcini? Not at all, it required a discipline in life style from food, to taking care of herself, to hard intellectual work every day.

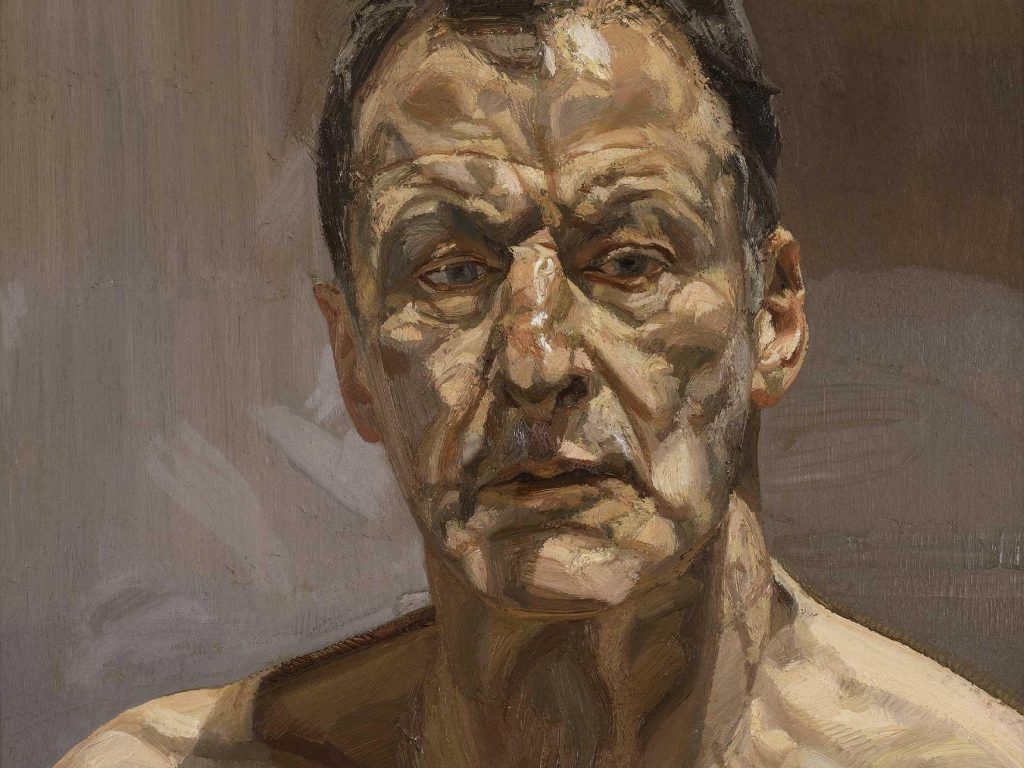

These lines are devoted to all elderly people who despite their bodies falling in pieces, as Lucien Freud painted in his portraits, are practising every day, doing soft gym, cross words, helping with grandchildren and great grandchildren, writing, lecturing, cooking, cleaning… their narratives are important and witnessing the wish to leave a legacy, when the last years are fading away.

And we wish for a more inclusive society which included these old fragilis and strong people, since death cannot become a better solution to aging and the related dark side, the racism by the community, the ageism.