In Gaza, civilians and anyone attempting to provide assistance—doctors, nurses, rescue workers, and journalists—have become deliberate targets.

The deadly double-tap strike and the paralysis of rescue operations have become common practice: this tactic—where a second bombing hits the same target shortly after the first, just as rescuers and journalists arrive—is documented in at least 24 cases since October 7, 2023. This practice multiplies casualties, renders aid efforts ineffective, and has a paralyzing psychological effect: it turns every rescue attempt into a potential suicide mission and creates an insurmountable ethical dilemma between humanitarian duty and the instinct for survival (as is happening now with the Flotilla).

The narrative of the martyr is spreading: in this context, beyond the physical war, a dangerous narrative conflict is unfolding. Rescue workers and healthcare personnel who are killed are systematically labeled not as neutral civilians but as “martyrs” or “sympathizers” of armed groups. This rhetoric, which equates humanitarian action with support for terrorism, turns a doctor pulling a child from the rubble into a legitimate military target. It’s a strategy designed to delegitimize victims and provide a legal justification for attacks that would otherwise clearly violate international law. It also gives moral “permission” to soldiers to kill aid workers. War is not fought only with weapons, but also with propaganda that manipulates the meaning of actions.

The numbers are staggering: Gaza’s Ministry of Health estimates over 1,500 deaths among doctors, nurses, and first responders. WHO data reports 680 healthcare workers killed. Each life lost is a fatal blow to a healthcare system already in collapse, with 94% of hospitals damaged or destroyed, and over 1,900 recorded attacks on healthcare facilities.

The Rebirth of Testimony Amid Silence

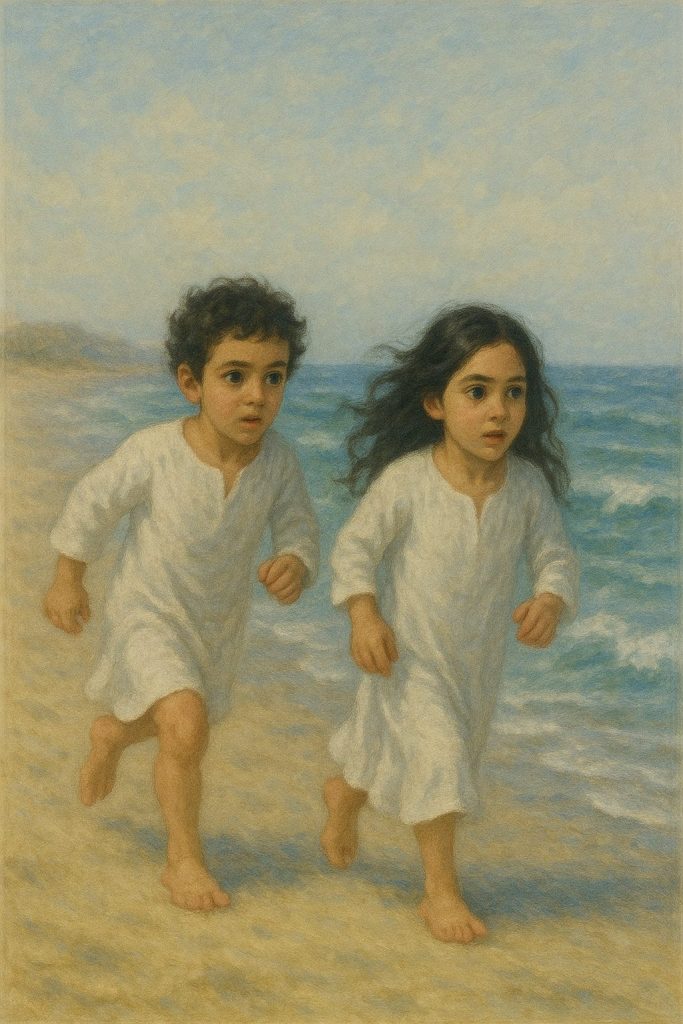

Even though 237 journalists have been killed, suppressing direct eyewitness accounts, the truth finds alternative paths. The film “The Voice of Hind Rajab”, awarded the Silver Lion in Venice, becomes the cry of a little girl trapped under the rubble, giving voice to those who risk remaining invisible behind the numbers. When eyewitnesses are silenced, art takes on the burden of memory, turning statistics into a human experience we can all identify with.

In this scenario, what’s under attack is not only a territory but the very concept of humanity. The Geneva Conventions were created to set limits on the cruelty of war. In Gaza, those limits have been exceeded, but testimony, in all its forms, continues to fight to reaffirm them. And yet, this reality surpasses all imagination for those of us watching from afar, in a country where civilians feel spiritually close to the victims, and where much of our national healthcare system supports the cause of the population. It is no coincidence that healthcare workers promoted the national day of fasting in Italy, as a symbol of the hunger that debilitates Gaza’s population, leaving them unable to move or mobilize, but to go where? “Escape” only means displacement within the Strip, not outside of it. There are no open humanitarian corridors: the crossings into Israel are closed to Palestinians, and the passage into Egypt is shut or has extremely limited access. UN agencies continue to say “there is no safe place” in Gaza, yet forced displacements are still ordered to designated areas in the south and along the coast. Toward nowhere, or toward humanitarian organizations, themselves the target of repeated double-tap strikes.

I feel the need to write these lines because I’ve discovered that many of us are unaware of the double-tap strategy: it struck me that it wasn’t the Israelis who first used it in Gaza; rather, it originated and has been documented in countries such as Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, and Pakistan…

And in the past?

Though with violent exceptions, there once existed a code of honor. And here in Gaza, that code has been abandoned.

But let’s look to the past. In all wars,a ccross history, codes of honor were not just a set of rules to restain violence: they were shared narratives that trasformed actions into symbols. In the Middle Ages, the code of chivalry dictated that a knight should spare an unarmed enemy; in doing so, he wasn’t simply performing a practical act, but forging the legend of himself as a man of honor. In the Bushido tradition, a samurai who showed mercy to a vulnerable opponent was not seen as weak, but as embodying the highest narrative of a discipline that separates strength from cruelty.

In these examples, it’s not the act itself that speaks, but the meaning the community assigns to it through storytelling. It is narrative, in fact, that determines whether a value is “good” or “bad.”

If the values conveyed by the narrative are just, the action becomes a sign of humanity; if the values are distorted, the same action is transformed into monstrosity. Narrative, therefore, does not merely describe reality: it actively shapes its ethical meaning.

In this sense, the Geneva Conventions did nothing more than codify what the ethics of various cultures had already intuited: that the nature of war should not be left to brute instinct, but should be framed by a system of meaning that gives value to actions. When rescue is narrated as an act of humanity, someone who risks their life to treat the wounded is a hero; when it’s framed as complicity with the enemy, that same act becomes a pretext for a calculated double-tap strike.

The Conventions put this deep awareness into black and white: the values collectively narrated are the very foundation of Humanitas.

That is why war crimes are not just violations of a treaty: they are the reaffirmation of those ‘anti-values’—cruelty, contempt for the innocent, the abolition of all limits—that every code of honor, from chivalric to Bushido in Japan to Islamic (do not strike women and children), was created to banish. They are monstrosity elevated to a system.

Maria Giulia Marini