………you are a young student, aged 18 years old, and due to your brilliance at examinations you have been accepted into medical school. You arrive at medical school as a brilliant student, but your knowledge of life is restricted to classrooms and studying in your bedroom. You applied for medicine because your parents wanted you to follow in your grandmother’s steps, and also because your teachers saw that you were capable of achieving the grades necessary to get in. It never occurred to you that studying medicine would be any different from studying chemistry or physics, and you had not really thought about what it would entail apart from the vague answer you gave in your very short interview that you wanted to ‘help people’. In your second year you start seeing patients, and you begin to realise that this is not the same as studying at school; the people you see in the beds are very ill, frightened and unsure of what will happen. When you try to speak with these patients, with your seniors behind you watching your every move, you too feel scared, become lost for words, do not know where to look, or where to put your hands. At last, you pluck up the courage and say something ridiculous and inadequate; brusque even. The old lady in the bed, dying from breast cancer, touches your hand and says, ‘Don’t worry, dear’. But you do. And after the round, and when the consultant does not see you, you crawl to the bathroom, lock yourself in the cubicle and cry for what seems like hours.

This is not a real case; this is fictional, but it could apply to thousands of medical students around the world who do not really know what they are getting themselves into when they begin medicine. And how can they? Their only knowledge of a hospital is when they went to see their baby brother born.

The renowned Catalan doctor, Jose de Letamendi, (1828-1897),

‘a wise professor of medicine, polyglot, notable mathematician, philosopher in his own way, composer and accomplished pianist, who also painted and drew; an illustrious Wagnerian pioneer.’ [1], is reputed to have said, “El médico que sólo sabe medicina; ni medicina sabe” “The doctor who only knows medicine; does not even know medicine.”

So, we come to fictional and non-fictional illness narratives; what are they and why are they important? An illness narrative is a type of storytelling that focuses on the experience of illness. These narratives can be either factual or fictional.

- Factual illness narratives are real-life accounts, often found in memoirs, autobiographies, or patient stories. They provide a personal perspective on the experience of being ill, including the physical, emotional, and social challenges faced by the individual. Examples of non-fictional illness narratives include memoirs like When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly by Jean-Dominique Bauby, and An Unquiet Mind by Kay Redfield Jamison[2].

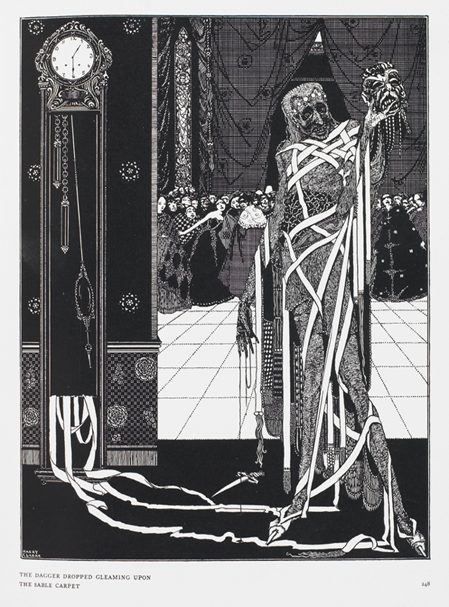

- Fictional illness narratives are imaginative constructions found in novels, short stories, plays, and poetry. In these narratives, a character’s journey through illness is a significant part of the plot and themes. They explore illness by intertwining it with character development, themes of existence, and the complexities of human relationships. Some fictional examples include Albert Camus’, The Plague; Ian McEwan’s Saturday or Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of Red Death.[3]

Both types of illness narratives offer valuable insights into the human condition, highlighting themes of vulnerability, resilience, and the impact of illness on individuals and their relationships, and both kinds of illness narratives are important tools for all of us to learn about life and death. Illness narratives can expand our sensibility and even increase our empathy. Kavya Shree writes,

‘The world is a balance of good and evil, right and wrong, light and dark. In this context, living beings are either sick or healthy. Like being healthy, sickness or illness is part and parcel of life. Though people are expected to live a happy life, no man on earth has ever lived a healthy, disease-free life. Thus, illness is an essential part of a man’s journey of life’.[4]

Illness and death are both essential parts of our lives, and this perhaps is something that eludes young medical students, and by reading an ‘other’s’ experience they can learn so much, develop as human beings and as future doctors who will be dealing with persons struggling with illnesses. Illness narratives are essential for medical training as very often they can give the more personal account of an illness rather than the ‘biomedical’ version. As the sociologist Arthur Frank writes,

‘The postmodern experience of illness begins when ill people recognize that more is involved in their experiences than the medical story can tell’ [5].

But what happens when the doctor is the patient and writes the illness, as in the case of Paul Kalinthi’s When Breath becomes Air (2015). Kalanithi, M.D., was a gifted neurosurgeon and writer whose life bridged science and the humanities. Raised in Kingman, Arizona, he studied English literature and human biology at Stanford, earned an M.Phil. in history and philosophy of science at Cambridge, and graduated from Yale School of Medicine in 2007 with top honors. Returning to Stanford for neurosurgery residency and a neuroscience fellowship, he published extensively and received national recognition for his research. In 2013, at age 36, Paul was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. While completing his residency, he began writing deeply moving reflections on medicine, mortality, and meaning, which appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and other outlets. He died in March 2015, shortly before the publication of his memoir When Breath Becomes Air, now regarded as a modern classic. He is survived by his wife, Lucy, and their daughter, Cady.

As Shree states ‘One disadvantage is that the dividing line between fact and fiction, authenticity, and creation is usually blurred in these kinds of narratives’, and that ‘In this sense chronic illness narratives might be called ‘Factions’ rather than Fact or Fiction’. For me, the problem of ‘authenticity’ is, in some ways, an invented problem since all illness narratives have a degree of ‘artistic licence’ in that when you write, be it fiction or a true story, you cannot help but use your creativity. Some of us have a very high level of artistic creativity, others less so but we all use what we have. The important point to note is how these illness narratives can help tell the story of one person’s suffering; give another side, as it were.

Let’s return to our young medical student, who was left crying in the bathroom. I propose that they would learn so much by reading Kalinithi’s work of creative faction, since as Kumagai writes,

‘Empathy, which is at the core of patient-centered, humanistic approaches to medicine, is based on the vicarious identification with another individual’s suffering. Fostering this quality in physicians-in-training requires more than an acquisition of knowledge, skills in communication, or lists of codes of behaviour: it involves a transformation of perspective and activities that stimulate self-reflection and engaged discourse, an internalization of humanistic values, a critical exploration of one’s own and society’s assumptions, biases, and values, and a commitment to enact the values that the profession espouses.’ [6]

Learning is one of the most beautiful reasons for living and, if you are open to the world around you, you will always be learning but when you are younger learning can be very hard, and medical students are often thrown into the deep end of the swimming pool with no support……

Throw in an illness narrative; this may help them float.

Afterword

My maternal grandfather, Andrew McKie Reid, like Bryan McFarland was also President of the Liverpool Medical Institution founded in 1779. He was slightly older than my paternal grandfather and thus was involved in both world wars; his medical training being interrupted in 1914 to enlist and fight in the First World War, where he was involved in the horrors of the battles of the Somme, Messines Ridge and Passchendaele, and received the MC (Military Cross). He was gravely wounded in March 1918, a German soldier, believing him to be lying dead in no man’s land, used my grandfather’s pistol to shoot the three remaining bullets into his body.

In 1964 (the year I was born) he wrote the following about his experience 46 years earlier,

‘I lost consciousness and then came to and felt my breeches filling with blood. I thought the subclavian artery had gone and I managed to roll over, tear open my trench coat, tunic and shirt with my left hand and saw and felt blood spurting from the cavity round the fold of the right axilla. I plugged the hole with the third finger of my left hand and there it remained for two days. My life, or soul, or spirit, call it what you will, became dissociated from my body, and from a height of five feet I looked at the helpless body. [7]

This ‘illness narrative’ is part of me, part of my family heritage as it comes from my grandfather and his experiences during the First World War. Every time I read it, I learn something more, something different, but I am always affected by the determination and will to survive and live that my grandfather showed. When he was shot, he was in his early twenties, and he convinced the German surgeon who was about to amputate his right arm not to do so as he wanted to continue his medical studies at the end of the war. On returning to his home city my grandfather finished his studies and became an ophthalmologist. Eye surgery needs less movement.

Bibliography:

[1] https://www.lavanguardia.com/local/barcelona/20250522/10707262/doctor-letamendi-mezcla-sabio-extravagante.html (1828-1898)

[2] Kalanithi’s deals with terminal lung cancer, Bauby’s – the Locked-In syndrome, and Jamison writes about bipolar disease.

[3] Camus and Poe both write about plagues while McEwan touches on Huntingdon’s disease.

[4] P, Kavya. (2021). Illness As Narrative Strategy: An Account of Illness Narratives and Popular Fiction. Bioscience Biotechnology Research Communications. 14. 178-183. 10.21786/bbrc/14.8.41.

[5] Frank, Arthur W. (2007) Stories and healing: observations on the progress of my thoughts. Anchorage.

[6] Kumagai, A. A Conceptual Framework for the Use of Illness Narratives in Medical Education. Academic Medicine. 2008

[7] McFarland, J. (2024). Humanism in surgery: Reflective dialogue across Arts, Humanities and Health Sciences. Springer Nature.