Languages of Care, by Maria Giulia Marini: the accurate and balanced view on Narrative Medicine in the healthcare ecosystem.

Susana Teixeira Magalhães, Researcher at the Institute of Bioethics of the Portuguese Catholic University

and professor at Fernando Pessoa University.

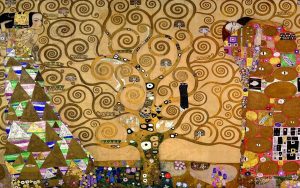

Maria Giulia Marini has chosen Johannes Vermeer’s painting “A Woman holding a balance” as the cover of her book “Languages of Care in Narrative Medicine: Words, Space and Time in the Healthcare Ecosystem”. The reason for this selection lies in the sense of stability and rythm that this painting brings forward, with the main character, the woman in a blue jacket holding the scales at an equilibrium, focused on seeking the balance that this book also aims and succeeds to achieve. Writing on this outstandinga book, I remembered the Tree of Life by Gustav Klimt, because the integration of verbal and non-verbal narrative into the practise, the theory and the research in the field of healthcare is perfectly and poetically done by Maria Giulia Marini. The branches of Evidence-Based Medicine connect with those of Narrative Medicine and both of them root into the earth and reach for the sky, i.e, both of them accomplish what they are needed for: to care for the person within her/his cultural, social, personal, professional, and environmental context.

Klimt’s painting also has the quality of challenging us to spend time – from a Kairos approach within our Chronos limited life – seeking for all the layers of meaning that it portrays. While drawing our attention to the multiple symbols on the canvas, it also reminds us of our shared vulnerability, our mortality, by placing at its centre a black bird, symbol of death for many cultures. Languages of Care does the same: it makes us leave the confort zone of certainties, so that we can travel to the uncertain field of doubts and queries, of errors and mistakes, of our image in the mirror. This movement from the confort zone to the unconfortable one is made possible by the use of pratical examples and by the prompts given in the sections of practice time (which is actually the reflective room of each reader, mirroring the writing room of each health professional and care).

What is to be stressed is Maria Giulia Marini’s knowledge and experience in the field of narrative healthcare that allows us to:

– get clear definitions of the main concepts, theories and approaches used in Narrative Medicine;

– understand how narrative medicine can be effectively put into practice, not only with literary and other Arts resources, but also resourting to the most human tool and feature: language in its minimal dimension (the Natural Semantic Metalanguage), the bridge that fills in the gap within all the different cultural contexts of narrative medecine;

– integrate Evidence-Based Medicine and Narrative-Based Medicine within this brilliant concept of Languages of Care, which are the root of Narrative Healthcare;

– question our own words, space and time when we care for the others and are cared by the others.

I strongly recommend the reading of this book by all health professionals, health students, carers, politicians and decision makers in the field of Healthcare.

The balance of the ecosystem will only be achieved if we are able to understand the anatomy of the stories we tell and are told when we get ill and when we take care of those who suffer the experience of illness.

A Commentary on Space, Time, and Balance

Stephen Legari, MA, MSc(A), ATR, ATPQ, CFT, Programme Officer, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

There are two chapters from Maria Giulia Marini’s Languages of Care in Narrative Medicine that I would like to offer reflections on. These reflections are contextualized within my own work as an art therapist working in at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) and it is my hope to convey something of the resonance, and indeed affirmation, I felt from Marini’s text. It should be noted that this commentary should not be read as expertise but rather from the perspective of one who marvels at the human will toward healing and the structures which may support this capacity. I am grateful for the opportunity to share these reflections within this forum of discussion.

If I take my point of departure that the aim of Narrative Medicine is to supplement evidenced-base medicine (Marini, 2019), then I find common ground in the aims and applications of art therapy. In my profession, we seek to use the created image as a container for that which does not have words – or does not have words yet. The client who has suffered through illness, who has struggled with the identity of one who is ill or sick, is entitled to the abstraction that comes with feelings of devastation; of a body that has been betrayed. And they are also entitled to the time it takes to construct a language that represents their experience, identity, and emerging sense of self.

Space is important to Marini, and important to health and healing. Where I work, I am surrounded by beauty. A fine art museum is conceived to support its collection but also those that consume it. Every detail informs curation and the experience of the viewer, visitor, scholar, family, and lone wanderer is considered. It is little wonder, then, that we have begun to imagine the potential of these spaces as supportive, therapeutic environments (Hamil, 2016). I can say that practicing therapy in a fine art museum is very different from the treatment room of a vintage hospital or the empty classroom of an old school. In the museum, I am joined by my environment in supporting the participant rather than working to forget or deal with the space’s lack of hospitality.

As we witness new hospitals and clinics take shape, the role of art, nature, and space have taken on new importance. What was once a passing thought in the form of a cart full of framed pictures intended to brighten the patient’s room has evolved to regard the interplay of architecture, material, light, air, text, and art. The patient’s health, then, can be seen as taking shape within this interplay and that the clinic and hospital must be considered as venue rather than a building. And so, as the venue moves towards statements of beauty, then we can begin to imagine spaces as holding empathic capacity.

The subject of space leads me to my next reflection on the pilot study and the storyline in Chapter 3 (Marini, 2019). At the MMFA we have been working with women living with breast cancer for 1.5 years and are currently researching their lived experience in a museum art therapy programme. Appropriately for this discussion, much of our data will come through story. In revisiting the pilot study, I reencounter my initial awe in the words of the 54-year old Portuguese woman who testifies to her own experience using the illness plot. In response Marini writes:

In this narrative, a human being is telling her own story, with the richness of the ambivalence of the emotions, even accepting the potential conflicts; on one day, she feels the joy of tasting every minute of life, and on the other, she wishes to die. This has to do with narrative, which is very often complex and full of inconsistencies as human life could be especially after so many traumatic years (Marini, 2019, p. 31).

There is a remarkable alignment in themes that we are observing with our own pilot study that directly relate to Marini’s reflection. In art therapy, whether through the use of theme, directive, or free association, there is always an important tension between providing just enough structure – sometimes called the frame or container, for the client to find their own expression. Too much direction and the expression becomes encumbered by the therapist’s own vision. Too little, and the client can feel lost in the face of a blank page. I see alignment, then, in the parsimonious illness plot and our own theme-based museum art therapy sessions which include looking at art, making art, and reflecting on it all.

As I am writing this commentary from a fine art museum, it behooves me to comment on the cover of Marini’s book. With little effort we know we are looking at a Vermeer, in this case Woman Holding a Balance which has also been called Woman Testing a Balance. The quality of light is unmistakable of the Dutch master. Marini, in her preface writes “The scales in her right hand are at equilibrium, indicating her inner state of mind. The woman is focused on seeking the balance; thus, I consider her as my model in writing this book (Marini, 2019, p. xi)” But what I would like to propose is a reading of the painting within Marini’s thesis, that basic language can facilitate empathy and human connection and that these qualities can have a transformative effect on the theory and practice of medicine. And, additionally, that art can provide us with the raw materials to help construct our stories.

If we turn our attention to the vanishing point of the painting, we are holding our gaze upon the delicate hand of the woman who in turn holds an empty balance. What is she weighing? What is her narrative? It is difficult to entirely ignore the immense weight of Christ’s judgement that hangs only inches from her shoulder – but his presence needn’t overshadow the nuanced, almost existential moment we come upon. If we could ascribe her a language, what would she say? Her gaze might suggest she is more reflective of the object’s symbolism than its utility, and so she is weighing the very air that surrounds her. If we project an identity of one who has suffered onto her, then the balance she weighs might be her very own life. And her life may be one that is out of balance or has had it restored. If you were to ask her to share her story, where would you wish for her to begin?

The honour with which Marini ascribes to the patient narrative reminds me of Ray Williams’ championing the personal response of the museum visitor (Williams, 2010). Williams, a pioneer in museum education, provides an array of prompts for the visitor that asks them to seek out memories, association or contextualized states such as: “Find the work of art that you would choose to share with a depressed friend. Think about the reasons for your choice. . . .(Williams, 2010, p. 96).” Here we can find elements of a plot that guides the visitor to construct their own narrative. What we learn from these reflections doesn’t diminish the importance of art history, it enlarges it. Just as what we learn from the narrative medicine doesn’t replace the clinical care, it humanizes it.

References

Hamil, S. (2016). The Art Museum as a Therapeutic Space. Expressive Therapies Dissertations. Lesley University Follow. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203978719

Marini, M. G. (2019). Languages of Care in Narrative Medicine: Words, Space and Time in the Healthcare Ecosystem. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94727-3

Williams, R. (2010). Honoring the personal response: A strategy for serving the public hunger for connection. Journal of Museum Education, 35(1), 93–101.

Neil Vickers, Professor of English Literature and the Health Humanities, King’s College London

Until now a tension has existed between proponents of evidence-based medicine and narrative approaches. In this brave and original book, Maria Giulia Marini uses the relatively new discipline of Natural Semantic Metalanguage as a bridge between these two areas. The language of care, she argues, is shared by professionals, patients and carers alike. A special feature of this book is its appeal to works of art as natural extensions of the language of care. Marini reads two classic novels by Virginia Woolf to explore the way time is experienced differently by sick people and their relatives, from, say, clinical professionals. She explores music, the visual arts and architecture as communicative systems that can structure and contain illness experiences. And she revises the intellectual foundations of narrative based medicine in the process. As healthcare systems become jargon-laden behemoths, they alienate patients and clinicians alike. This book takes us back to something basic. It attempts to bridge the gap between patients and clinicians by harnessing their joint commitment to hope, coping and kindness, by teaching both new languages of care. A must-read book for health humanists, clinicians and linguists.